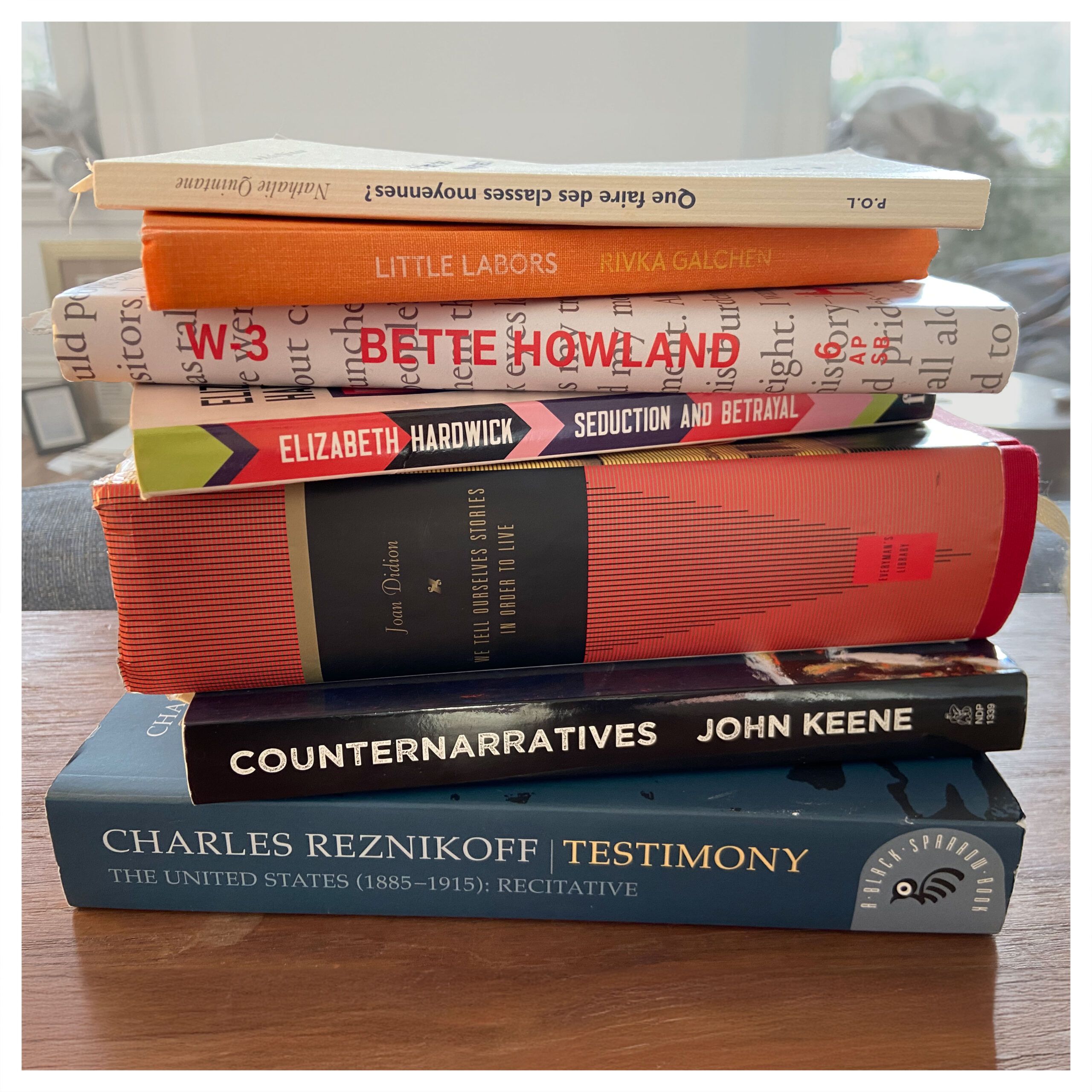

Rivka Galchen’s Little Labors and John Keene’s Counternarratives, very differently, helped me by demonstrating prose techniques for transposing daily reality or history to literature’s language, for crystallizing and, somehow, dignifying that reality. I’d encountered each in New York City, where I had been working as a freelance writer as well as at some other jobs, shortly before moving back to Paris in 2018, to re-report Precarious Lease. The first is micro, offhand; the essayist’s new baby has left her with only enough writing time for vignettes; this places her within a long lineage of female authors (she discusses Sei Shōnagon’s The Pillow Book). The second is definitely macro: lavish, revisionist, visionary.

Nathalie Quintane’s Que faire des classes moyennes? – the title translates as “What to do about the middle classes?” – marshals information with an inventiveness that, at a certain, key moment, illuminated opportunities.

Bette Howland’s W-3 – about life in the Chicago psych ward where she was confined at the age of thirty-one – is a work of prose whose precision is a way of thinking through shattering personal material with great idiosyncrasy of vision yet rendering it usable, self-sufficient.

I am a fan of Joan Didion’s political reporting, done later in her life; We Tell Ourselves Stories in Order to Live, her collected nonfiction, is pictured here. Elizabeth Hardwick’s Seduction and Betrayal is another all-time favourite. Missing from the photo, because I keep lending them out, are books by Renata Adler and Janet Malcolm. These are frequent references for American essayists today, when we can easily discern the compounding effects on writing of what Adler long ago, in her media criticism, described as ‘the rise of the byline’ – before Twitter or podcasts were even invented. The integrity of their sentences, an impersonal integrity, is a built-in aspect of these reporters’ pursuit of the truth.

Charles Reznikoff’s Testimony, which he continued to revise throughout his life, is the sediment of efforts of astounding persistence and integrity to extract beauty in the form of a renewal of the language out of documents that were byproducts of legal processes often of violence; speech and facts placed side-by-side renew the language, part of this book’s sweeping social vision.