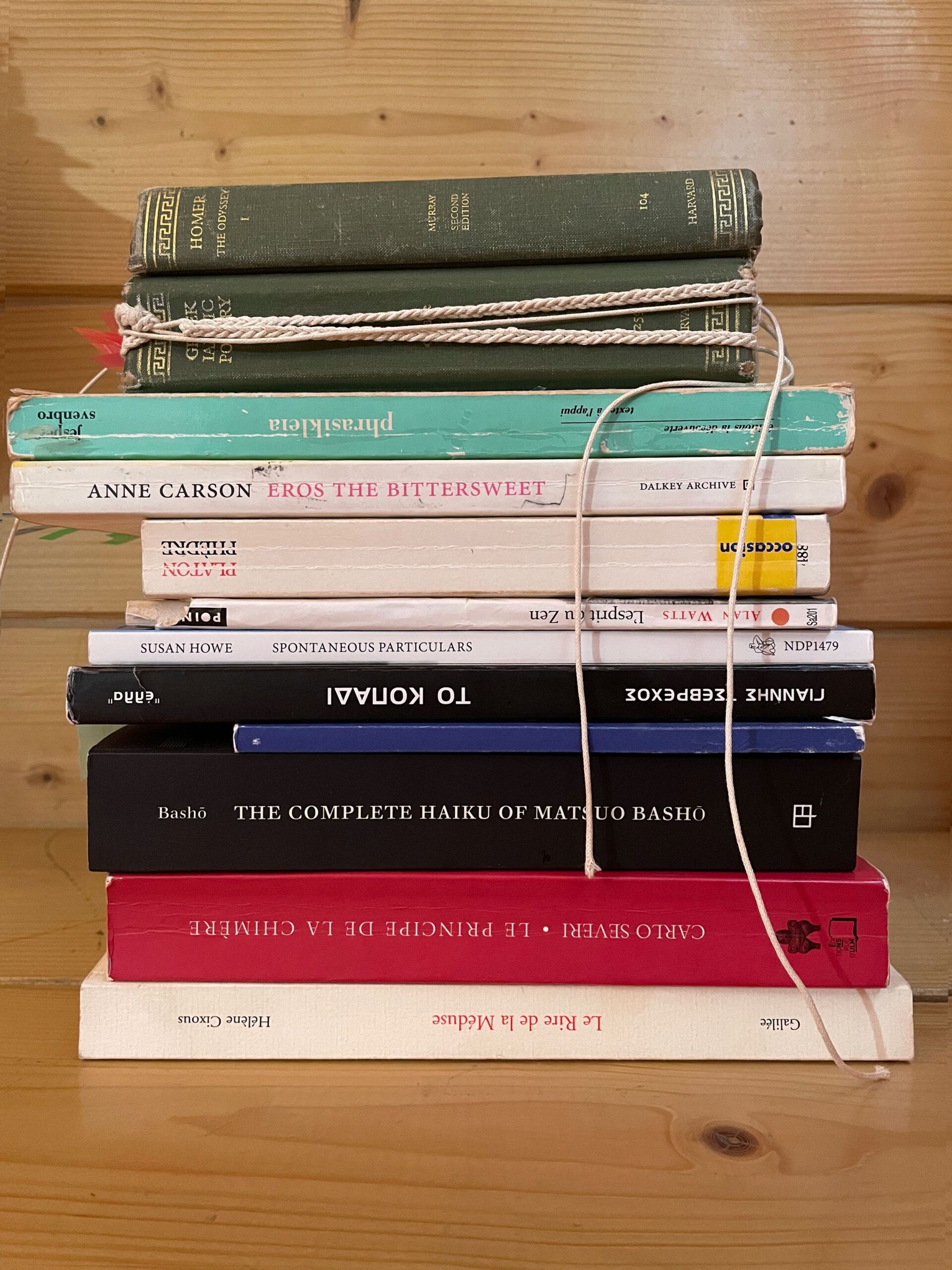

Phoebe Giannisi has written about the works that inspired the writing of the three collections that make up Goatsong, translated by Brian Sneeden.

Homerica

The Odyssey and the Iliad, of course. The Odyssey (Loeb Classical Library, 1995, tr. A. T. Murray revised by G. E. Dimock) is rewritten in Homerica as tales of return within the landscape of love, in a contemporary female voice multiplied by the voices of various female mythic Homeric personae. The Iliad is related to the place where I live, where Thetis, Achilles, Patroclus, Peleus, the cuttlefish and the wave are still present. I read it in the original and with the translation by Olga Komninou-Kakridi, the first woman to translate the epos into Greek (Zacharopoulos, 1954), many many years before Emily Wilson’s translation was published, though nobody here refers to her work. Hélène Cixous’ Le Rire de la Méduse (‘The Laugh of the Medusa’, Galilée, 1975; 2010) helped me understand the deliberating power of the feminine writing (écriture féminine), close to the female body, its language and desire. Jesper Svenbro’s, Phrasikleia (La Découverte, 1988;tr. Janet Lloyd,Cornell University Press, 1993) was the reason I started switching between different media for my poetry, introducing sound recordings of the poems that have been performed by me, alone, in the natural environment to which they belong. Thus, the original Greek book included a CD with the recitations, so that the poems could not only be read but also heard. (The poems can still be listened to here.)

Cicada

Cicada originated from an audiovisual installation at the National Museum of Contemporary Art, Tettix. Tettix was inspired by the association he association of the poet’s voice and the singing cicada as it appears through ancient Greek mythology, philosophy and poetry. A fragment of Archilochus – ‘you caught a cicada by the wing’ – guided me to the reading of the whole corpus of Archilochus in the Greek Iambic Poetry (ed. and tr. Douglas E. Gerber, Loeb Classical Library, 1999). An excerpt from Plato’s Phaedrus where Socrates narrates the origin of the cicadas, previously crazy for song and servants of the Muses, guided me to the reading of the French edition, published together with Jacques Derrida Plato’s Pharmacy (tr. Luc Brisson, GF Flammarion, 1995).In Eros the Bittersweet by Anne Carson (Dalkey Archive Press, 2009), I loved the whole writing of the book as a tale and an essay that mixes cicadas and poetry, where the seam is love. I also read a lot of Japanese haikus, since the cicada is as fundamental there as in Ancient Greek poetry, such as Basho: The Complete Haiku of Matsuo Basho (tr. Andrew Fitzsimons, University of California Press, 2022). Finally, the key concept of moulting, or the metamorphosis of the cicada’s bodies in order to sing, have sex, reproduce and die, led me to the reading of Jean Henri Fabre’s Book of Insects (1921) which I found online.

Chimera

This book explores the feminine voice, poetry as motherhood, and the animal–human relationship as observed in a group of Vlach nomad shepherds and their life with the goats. The Greek book The Flock, by Yannis Tsevrechos, a shepherd, is central to my understanding of animal husbandry. I have read a lot on the Vlachs, such as the Greek translation of the book The Nomads of the Balkans, An Account of Life and Customs Among the Vlachs of Northern Pindus by Alan John Bayard Wace and Maurice Scott Thompson, and other books by travellers in Greece during the eighteenth century that are present as voices in Goatsong, such as Ami Bou, Joseph Dacre Carlyle and Philip Hunt, Edward Daniel Clark, Leon Heuzey, Pouqueville and William Martin Leake. But the principle of polyphony, polyvocality, performativity, intermediality, the co-presence of multiple genres and the concept of the poetic book as a field made by a collage and/or assemblage process, originates in books such as Herman Melville’s Moby Dick, Susan Howe’s Spontaneous Particulars: The Telepathy of the Archives (New Directions, 2014), or the fantastic ethnographic book The Chimera Principle, An Anthropology of Memory and Imagination by Carlo Severi (The University of Chicago Press, 2015). Half of the lyric poems in the book were written in a summer while reading Alan Watts’ The Spirit of Zen: A Way of Life, Work, and Art in the Far East (L’esprit du Zen, tr. Marie-Béatrice Jehl, Points, 2005), that also speaks about how one can achieve living in the absolute now, the present. What is the present in writing? Do we exist in the present, or are we absent from it?