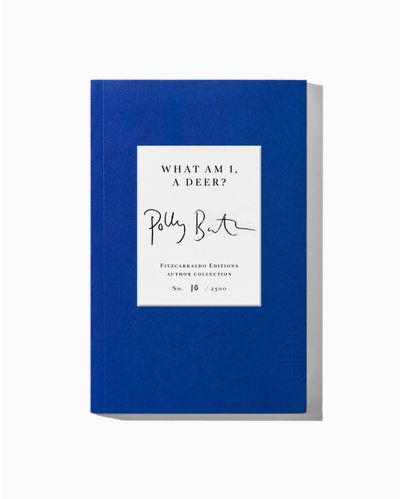

To celebrate the launch of Polly Barton’s What Am I, A Deer?, we are pleased to present the author collection, a series of occasional limited editions. Available exclusively through independent bookshops and on our website, with a single run of 2500 copies, each book is signed and numbered by the author on the front cover, and features sprayed edges in International Klein Blue. What Am I, A Deer? will also be available for pre-order in our fiction series soon.

What does it mean to lose yourself – and is that something you should be aiming for? A young woman with little interest in games takes up a job in Frankfurt at a famous gaming company, naively set on reinvention. On her morning commute, in the familiar clutches of tedium and self-loathing, she encounters a nice-eyed stranger who returns her forgotten umbrella and finds herself catapulted into a dizzying, year-long whirlwind of obsession – not just with this endlessly attractive spectre, but also with the feverish karaoke trips from which she draws the ultimate solace. With astonishing existential acuity, Polly Barton’s formidable debut novel renders the paradoxes of modern life in all its complexity, in deliriously self-conscious prose that is at once propulsive, titillating and bitingly funny. Echoing with the sounds of Whitney Houston and The Cure, reaching for the sublime in dark, sweaty boxes, What Am I, A Deer? is an exhilarating exploration of authenticity, fantasy, romance and intoxication.

‘Polly Barton’s What Am I, a Deer? is a beautiful piece of writing. An expansive, ambitious, witty stream of consciousness, this is a novel of, and about, translation – not just linguistic translation, but the acts of self-translation we are called upon to perform constantly in the modern world; translating our experience via the disparate languages of personal history, intimacy and class. This a novel that confronts formally the fractals of the self, in a voice that feels confident and yet insecure, cerebral and yet vulnerable. I loved it.’

— Susannah Dickey, author of Common Decency

‘I’m nuts about this book – a romantic comedy in the most wildly open and profoundly honest sense, a tour-de-force of the telling detail, an electrifying contemplation of our capacity for risk.’

— Jeremy Atherton Lin, author of Deep House

‘What Am I, A Deer? is profound, funny and true. With biting precision, Polly Barton marries the mundane with the transcendent, asking whether we can ever truly escape ourselves and the societal structures around us. Her prose is incisive, moving and beautiful – I loved it.’

— Jessica Andrews, author of Milk Teeth

‘In this sparkling novel of ideas, Polly Barton illuminates the shame of loving what other people love. How embarrassing to find your feelings perfectly summed up in a cliché, to sing a pop song and mean every word! In Barton’s hands, the cringeworthy passions become tools of self-knowledge and keys to a philosophy of the glorious banal. Gaming, karaoke, drunkenness, romance – there is nothing more revealing than the everyday escape.’

— Sofia Samatar, author of Opacities: On Writing and the Writing Life

‘A tender and nuanced novel exploring love, obsession, alienation, work and language with an immense sense of interiority. Polly Barton is capable of capturing fleeting, seemingly unremarkable feelings with perfect precision that cuts through to the reader’s very core – it made me stop and gasp several times as I recalled feeling exactly this way. It speaks to how we yearn to connect but often fail to truly see each other, and to the fundamental, gargantuan power of a crush. Karaoke will never be the same again!’

— Anastasiia Fedorova, author of Second Skin

‘The protagonist of What Am I, A Deer? finds herself both Schrödinger and his cat on entering the Frankfurt tram, the office, and the ‘black box’ of the karaoke booth; inside and outside simultaneously, trying to figure out whether she exists and in a state of tingling oscillation. Polly Barton is the maestra of controlled dissolution.’

— Jen Calleja, author of Fair: The Life-Art of Translation

‘What Am I, A Deer? is a playfully and obsessively observed novel about the pleasures and humiliations wrought from the foolhardy desire for recognition. Barton’s style of address strikes a brilliant balance between a camp-ish hyper-attention to the currents of power driving language and culture, and an earnest attention to the nuances of yearning. Like a Bernhard novel, What Am I is rich with inference, wacky enmity and genuine delight, the most striking of which is Barton’s exquisite command of her sentences.’

— Ellena Savage, author of Blueberries

Praise for Porn: An Oral History

‘I found my time with Porn: An Oral History unexpectedly moving. Barton’s candid, generous style as an interlocutor allows her subjects to move fluidly between their sometimes contradictory instincts and intellectual approaches in a way which feels revelatory and totally honest and human. A pleasure to read, and a vital new work for anyone interested in sex and its representation.’

— Megan Nolan, author of Ordinary Human Failings

‘I wasn’t expecting nineteen conversations about porn to make me feel as I felt after reading this book: grateful and hopeful and wide-open. Porn is a generous, intimate commentary on how we relate to one another (or fail to) through the most unlikely of lenses.’

— Saba Sams, author of Send Nudes

‘Porn is a fascinating, timely and humane testament to the value of uninhibited conversation between grown-ups. Its candour and humanity is addictive and involving – I couldn’t help but join in with the pillow talk! Reader, be prepared for your own store of buried secrets, stymied curiosities, submerged fantasies and shadowy memories to shamelessly awaken.’

— Claire-Louise Bennett, author of Big Kiss, Bye-Bye

‘Porn is many things – a prompt for dreams, the outsourcing of fantasies, a heuristic for the construction of desire – but it is often omitted from our “spoken life”, to use Polly Barton’s wonderful phrase. In Porn, she manages to get people to talk about this subject both omnipresent and omnipresently swept under the rug, peeling off her informers’ ideological armour to get at what they really like and why, and invites us to ask, without forcing any answers, what it means for an entire society to possess an entire guilty conscience surrounding a genre now constitutive of our understanding of what sex is.’

— Adrian Nathan West, author of My Father’s Diet

‘Polly Barton is a brilliant, learned and daring writer.’

— Joanna Kavenna, author of ZED

Praise for Fifty Sounds

‘Witty, exuberant, also melancholy, and crowded with intelligence – Fifty Sounds is so much fun to read. Barton has written an essay that is also an argument that is also a prose poem. Let’s call it a slant adventure story, whose hero is equipped only with high spirits, and a ragtag band of phonemes.’

— Rivka Galchen, author of Everyone Knows Your Mother Is a Witch

‘This book: a portrait of a young woman as language-learner, as becoming-translator, as becoming-writer, in restless search of her life. It is about non understanding, not-knowing, vulnerability, harming and hurt; it is also about reaching for others, transformative encounters, unexpected intimacies, and testing forms of love. It is a whole education. It is extraordinary. I was completely bowled over by it.’

— Kate Briggs, author of The Long Form

‘It seems fitting, somehow, that this marvelous study of the expansiveness and precarity of human communication is so woefully ill-served by a literal description of its contents. As in all great works of genreless nonfiction, all of the subjects Fifty Sounds is putatively “about” – Japan, translation, the philosophy of language – are inspired pretexts for the broad-spectrum exercise of an associatively vital and thrillingly companionable mind. This is a gracious, surprising, and very funny debut from a writer of alarming talent.’

— Gideon Lewis-Kraus, author of A Sense of Direction