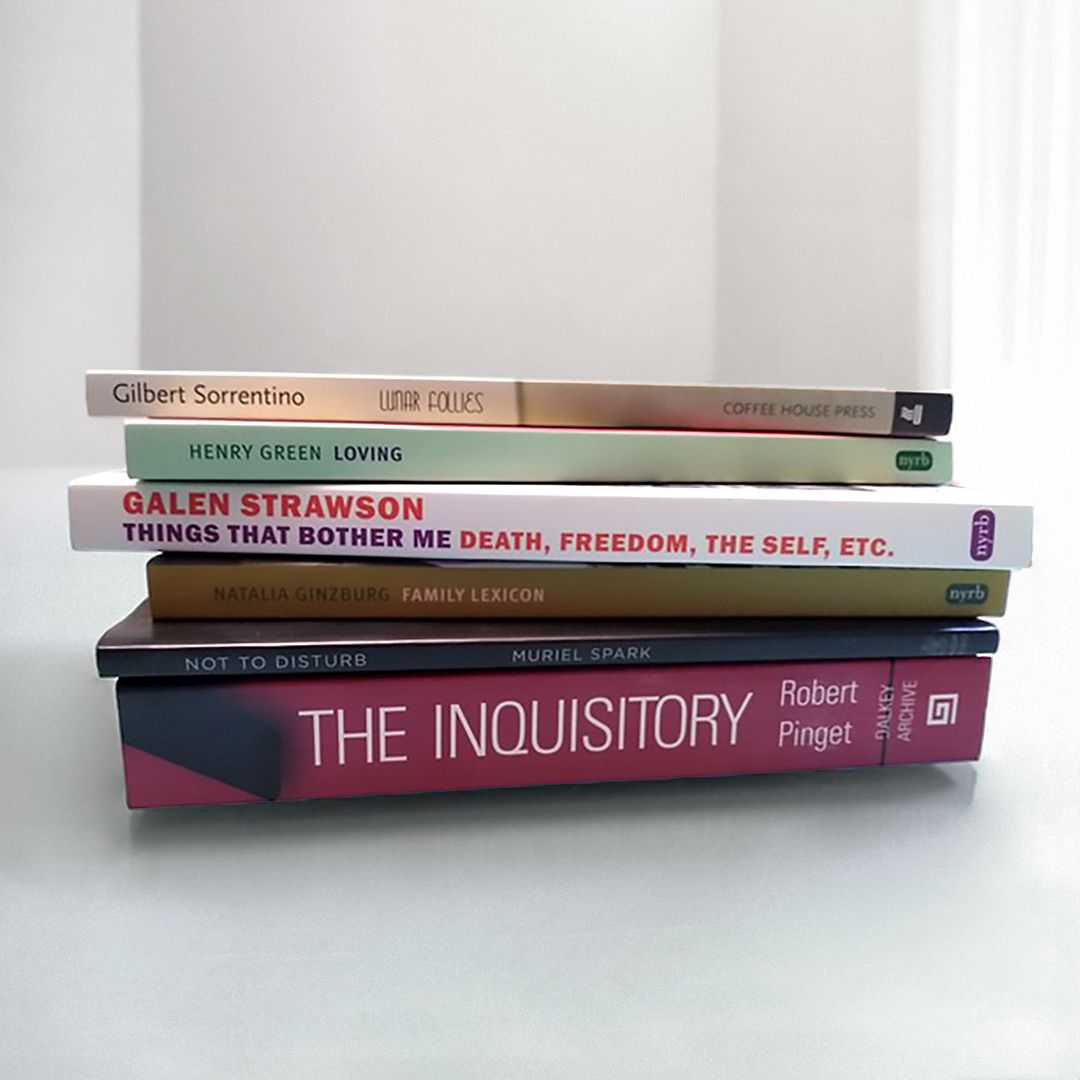

Family Lexicon by Natalia Ginzburg, tr. Jenny McPhee (2017)

‘If read as a history, one will object to the infinite lacunae’, writes Natalia Ginzburg in her preface to this extraordinary, episodic story of her remarkable family. The gaps are a consequence of her exemplary honesty – ‘memory is ephemeral’, as she says, and she resists any inclination to smooth over the unfilled spaces by means of invention.

The Inquisitory by Robert Pinget, tr. Donald Watson (2003)

The narrator of Tell might be a very distant cousin of the protagonist of Pinget’s masterpiece, in which a garrulous manservant is interrogated at length about offences that may or may not have occurred in his employer’s château. The old man puts on a wonderful performance, a torrential recitation that deluges his questioner with more information – or misinformation – than any listener could possibly retain.

Loving by Henry Green (2011)

Henry Green is someone to whom I frequently return – he’s a superlative and eccentric craftsman, and he writes dialogue that scintillates. Doting, his final novel, is a Mozartian delight, in which every page consists almost entirely of direct speech, but the Green novel that has closest affinities with the big-house setting of Tell is Loving, a delicious concoction of below-stairs intrigue, gossip and sexual tension.

Lunar Follies by Gilbert Sorrentino (2005)

The narrator of Tell, who is deeply suspicious of the art world in which her employer is a significant player, might relish the virtuosic satire of Sorrentino’s collection of essayistic fictions, which presents us with a gallery of pretentiousness in multitudinous forms, all of them parodied in prose of baroque brilliance.

Not to Disturb by Muriel Spark (2018)

Muriel Spark is another novelist whose work I read over and over again – I love her extreme concision, the severity of her wit, and her impatience with certain conventions of fiction – her disdain for suspense, for example. Not to Disturb isn’t the most highly regarded of her novels, but it’s one of my favourites. An off-kilter detective story, it’s set in a Swiss mansion, where the Baron and Baroness have shut themselves in the library with their attractive young secretary. Awaiting the inevitable but obscure crime of passion, the servants prepare to cash in on the imminent disaster. Mock-gothic elements are also at work – there’s a lunatic brother in the attic.

Things that Bother Me by Galen Strawson (2018)

I have never been persuaded by the widely accepted idea that one’s life should be understood as a story, and that a sense of oneself as a clearly defined protagonist of that story is essential to a meaningful existence. The narrativist fallacy is one of the topics that philosopher Galen Strawson addresses, with characteristic force and clarity, in this astringent collection. He also discusses the intractable problem of the nature of consciousness – a thing that bothers me too.