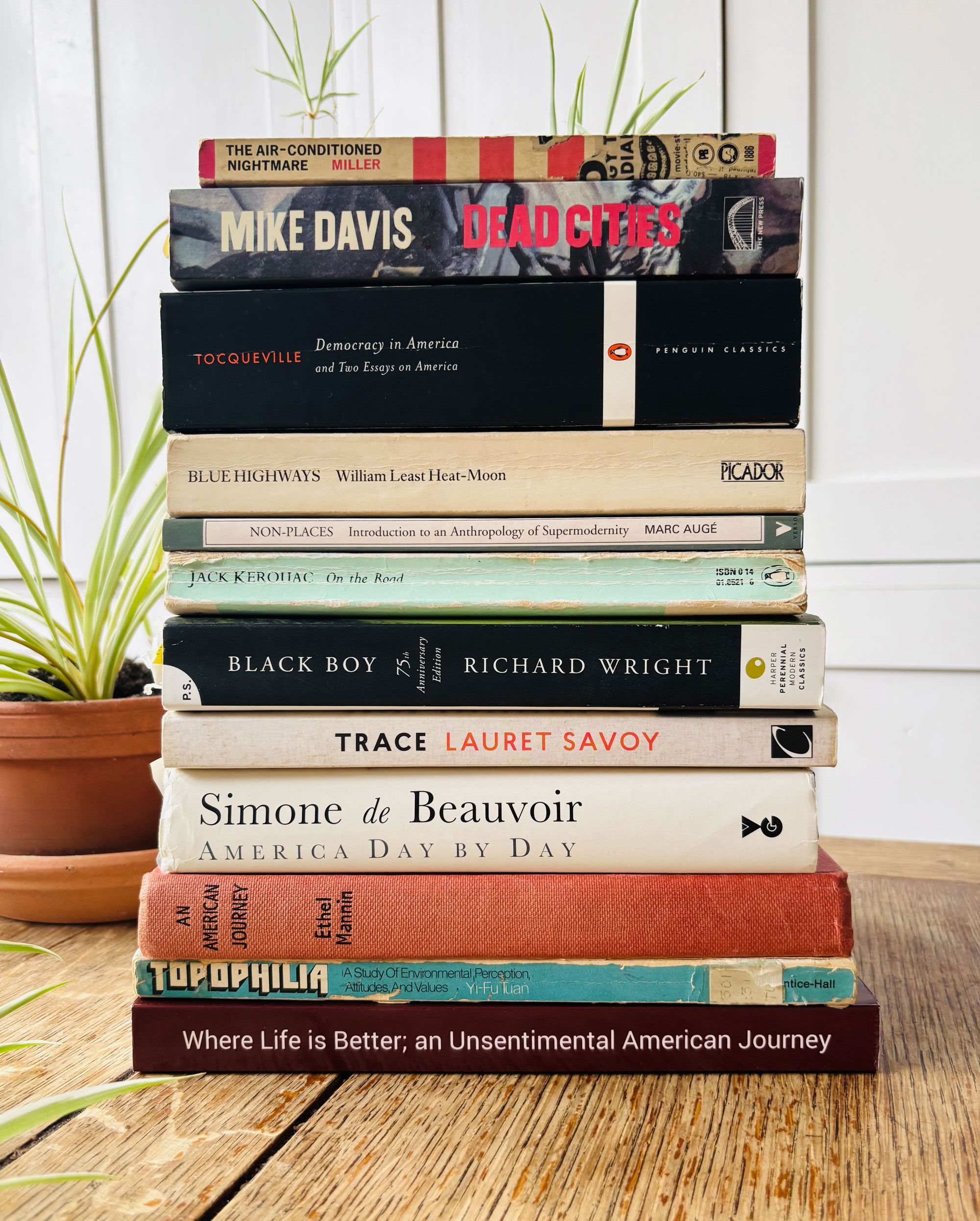

A list of works that inspired the writing of Joanna Pocock’s latest book, Greyhound.

Combining memoir, reportage, environmental writing and literary criticism, Greyhound is a moving and immersive book that captures an America in the throes of late capitalism with all its beauty, horror and complexity.

Non-Places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity by Marc Augé, tr. John Howe (1995)

It was important for me to think deeply about place and about how we remember it and move through it – not just the beautiful or pastoral places, but the transient and unattractive ones. The Greyhound bus I travelled on is both a symbol and a means to get from A to B. Augé contextualizes place in a way that seemed so apt for the non-places I was moving through: the gas station forecourts, the sprawl, suburbs, motorways and underpasses – and the temporary communal space of the bus itself.

America Day by Day by Simone de Beauvoir, tr. Carol Cosman (1947)

When I was writing Greyhound, this book was out of print. I managed to find a used copy on eBay (it’s being republished by Penguin in August 2025). Some of her travels on this 1947 lecture tour are by Greyhound, which I found fascinating. Although the buses and the stations are described as being beautifully elegant, de Beauvoir reminds us that racial segregation was still being enforced. Running just below this elegance is a stream of injustice. (She mentions trying to see Henry Miller’s house when she goes to Big Sur, which I found amusing – another satisfying research overlap.)

Dead Cities by Mike Davis (2002)

I don’t think you can write about the United States without reading Mike Davis, the ‘prose laureate of America’s decline’. Davis is unique in his ability to peel back the layers of history, culture and politics to reveal how American idealism has shaped the landscapes and its people in a way that both deepens and redefines the word ‘America’.

On the Road by Jack Kerouac (1957)

It’s embarrassing how much I love this book. Kerouac’s prose is like Jazz, full of improvisation, electricity and joy. He is searching for an America that feels just beyond reach. Like a horizon it dematerializes as soon as you arrive. There is a restlessness and a love for the road in these pages which encouraged me on in my own travels.

Blue Highways: A Journey into America by William Least Heat-Moon (1983)

‘A man who couldn’t make things go right could at least go,’ William Least Heat-Moon writes in Blue Highways. I knew this feeling well. Least Heat-Moon, who is of Irish and Osage ancestry, zig-zagged by car across the US in the hopes of escaping heartache. His route is not the usual east to west, but a circuitous journey. The result is a lyrical and beautiful portrait of the Americans who populate the lesser known parts of the country – places I, too, would be passing through.

An American Journey by Ethel Mannin (1967)

Born in 1900, Mannin was a madly prolific author: she wrote six autobiographies and over a hundred works of fiction and non-fiction. Married twice, she had affairs with W. B. Yeats and Bertrand Russell. She crossed the United States twice by Greyhound and observed the US with a keen outsider’s eye. Like Simone de Beauvoir and Henry Miller, she wasn’t impressed with the air-conditioning, the superabundance of commodities and the racism she saw around her. (This one is out of print and in need of republishing with a good introduction.)

The Air-Conditioned Nightmare by Henry Miller (1945)

In The Air-Conditioned Nightmare, Miller angrily exposes the burgeoning social and environmental devastation that I came face to face with on the Greyhound bus. Miller’s fury at the American culture of convenience – and its wasteful throw-away mindset – stems from a deep optimism that there is a better way to organize society. On a purely formal level, his sentences sparkle and fizz. It’s a joy to read.

Where Life Is Better: An Unsentimental American Journey by James Rorty (1936)

Mysteriously, this book is out of print. I had to buy one of those badly-printed online facsimile editions. James Rorty (father of the philosopher Richard Rorty) was a radical, anti-McCarthyist, anti-Jim Crow writer and activist whose book about driving across the US is an excoriating examination of labour injustices and environmental devastation. (It is also a good candidate for being republished with a cracking introduction.)

Trace: Memory, History, Race, and the American Landscape by Lauret Savoy (2015)

Savoy is a clear-eyed thinker who writes about the naming of places, the structures of power and the narratives around place that we embody (often unconsciously). She brings to the fore overlooked narratives that enrich our understanding of how the US has dealt with racial inequality, social injustices and the mapping of its lands. I can’t think of another book that comes close to Trace in terms of a rethinking of how the United States has become what it is today.

Democracy in America by Alexis de Tocqueville (1831)

De Tocqueville’s first-hand accounts of the treatment of First Nations people are devastating and yet crucial to an understanding of the colonial American project. In his examination of democracy – and its implementation – with all the optimism and hubris involved in such a project, you can vividly see the seeds of today’s America.

Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, Attitudes and Values by Yi-Fu Tuan (1974)

With chapter headings like ‘The Ideal City and Symbols of Transcendence’ and ‘American Cities: Symbolism, Imagery and Perception’, I knew Topophilia would be an important part of my research. At the heart of Yi-Fu Tuan’s book is the question: ‘How do we perceive, structure and evaluate our human-made and natural environments?’ – a question that was uppermost in my own mind when I was riding the Greyhound looking out onto spaces that, despite being designed, often looked forgotten and accidental.

Black Boy by Richard Wright (1945)

Once banned and now considered a classic, Richard Wright’s autobiography, Black Boy, is a window onto the African American experience of growing up hungry and poor in the American South as well as being a work of beauty and formal invention. His prose is clear and tight and the narrative traces the story of a brilliant writer determined to find a place in a hostile America. Simone de Beauvoir describes her budding friendship with him in America Day by Day (a satisfying research overlap.)