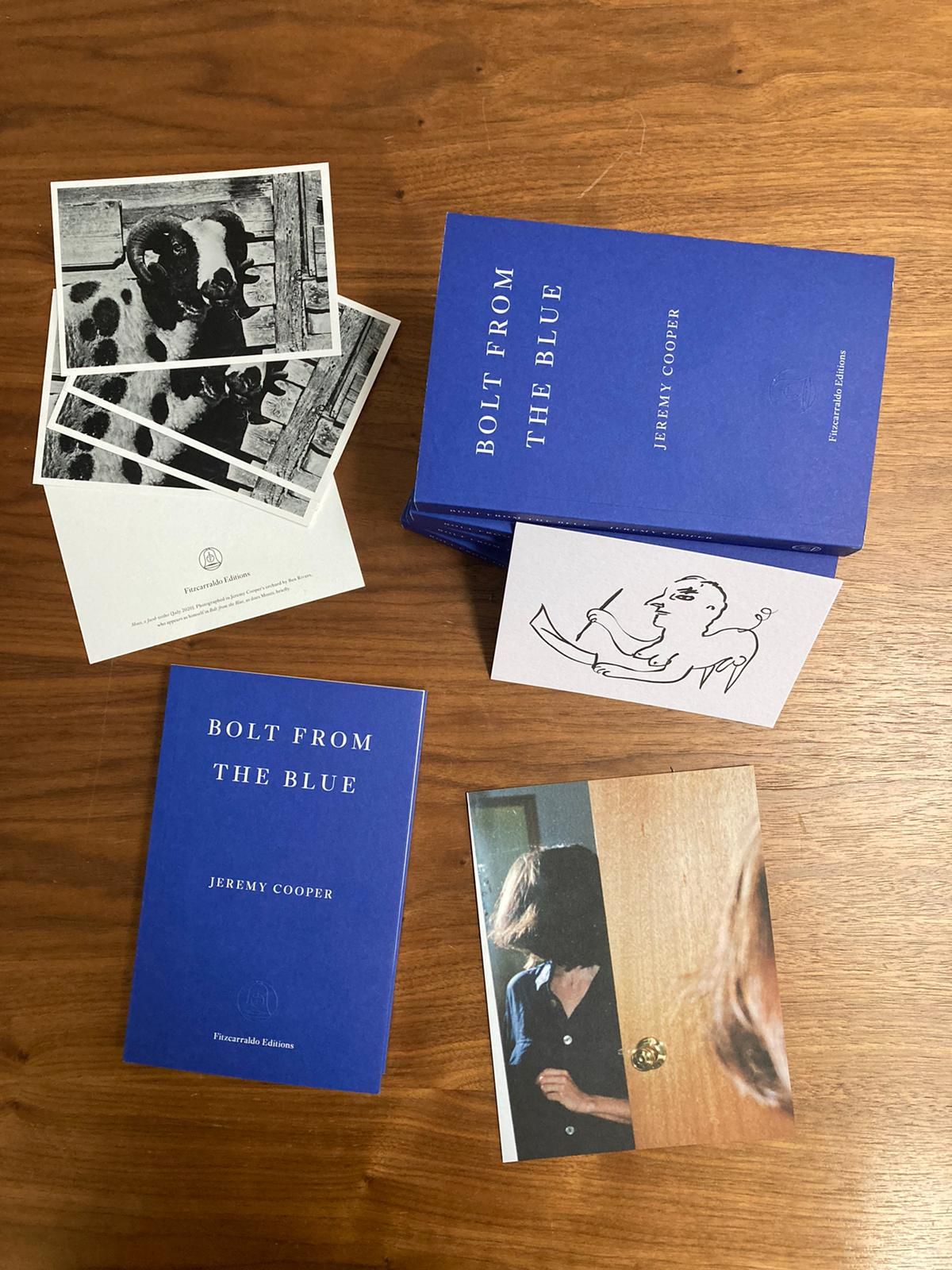

In Bolt from the Blue, Jeremy Cooper, the winner of the 2018 Fitzcarraldo Editions Novel Prize, charts the relationship between a mother and daughter over the course of thirty-odd years. In October 1985, Lynn moves down to London to enrol at Saint Martin’s School of Art, leaving her mother behind in a suburb of Birmingham. Their relationship is complicated, and their primary form of contact is through the letters, postcards and emails they send each other periodically, while Lynn slowly makes her mark on the London art scene. Here, Jeremy Cooper takes us through some of the postcards that appear in the novel.

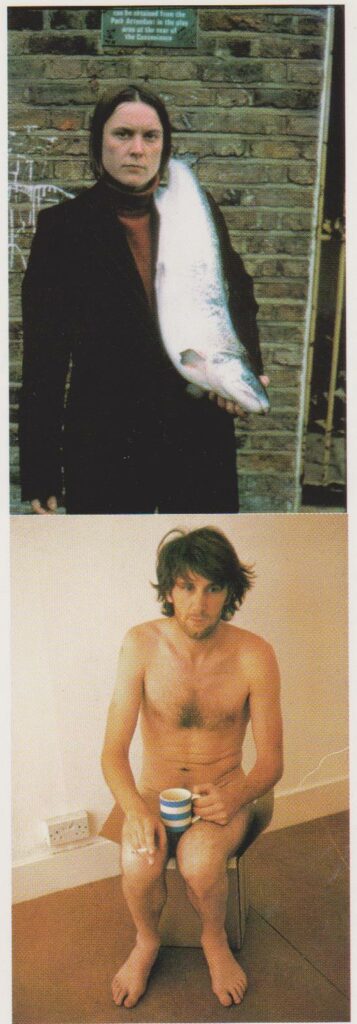

All my books, sixteen or more publications to date, novels and non-fiction, are centred on subjects I know and care about. In the case of Bolt from the Blue, the world inhabited by Lynn Gallagher is personally familiar to me, her progress as a young artist in London from the mid 1980s till the death of her mother in 2018 is informed by my friendship with artists of her generation, several of whom are named as themselves in the novel. Although I did not think of this when settling down to plan the book, in the course of writing it I decided to lend Lynn one of my more recent key interests: the collection of artists’ postcards. Being an artist, it soon became clear that Lynn would need also be the maker of some of the postcards she sent to her mother over the years, and instead of inventing spurious and possibly inadequate works I pretended it was she who created the examples from my collection. For instance, the painting on the Gordon Matta-Clark postcard described on page seventy-three of the novel is in fact the work of a young Spanish artist called Cristina Garrido, an MA graduate from Wimbledon College of Art, in a technique she used in another of her manipulated postcards, part of my gift in 2019 to the British Museum.

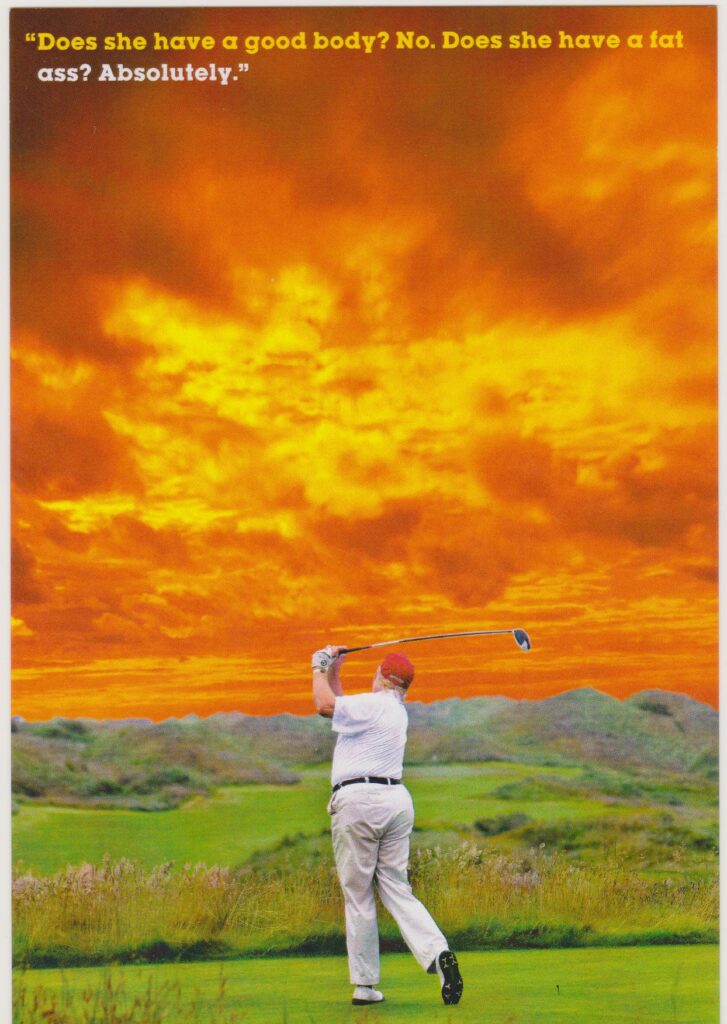

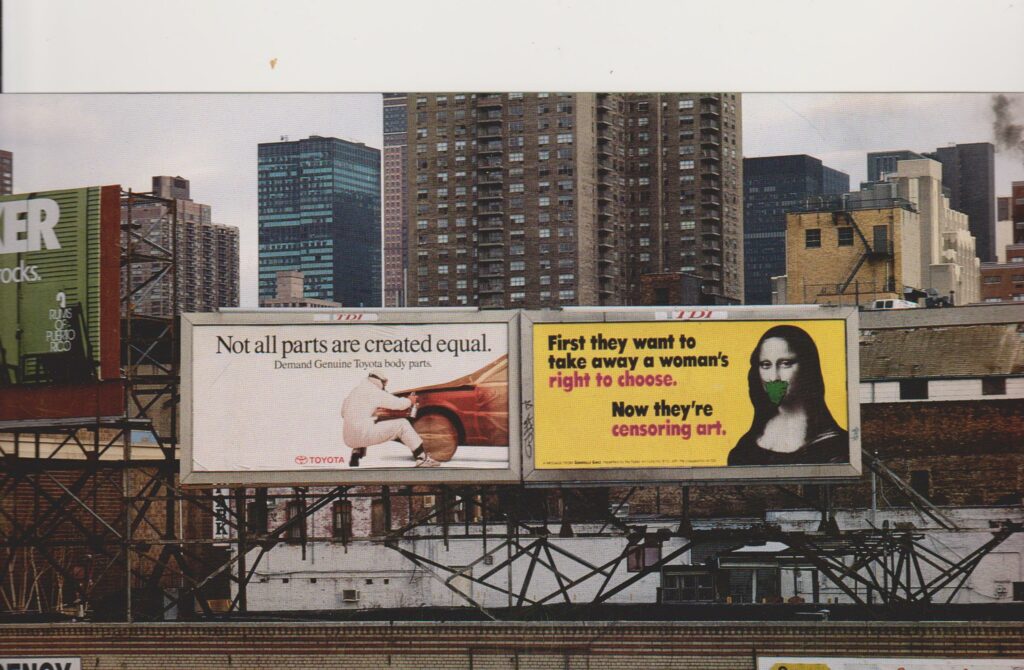

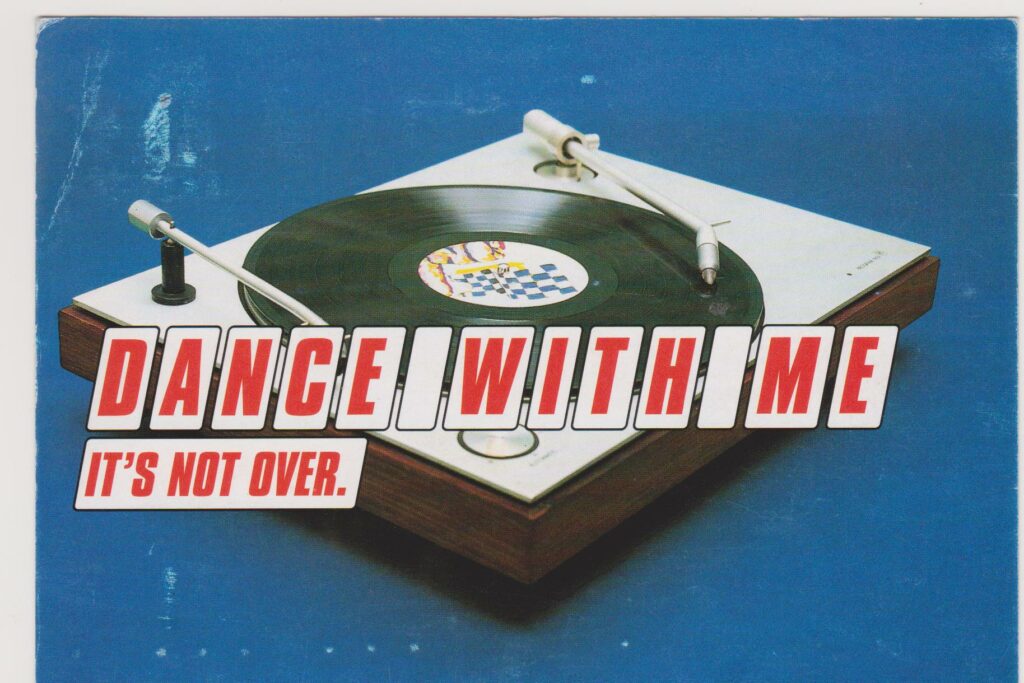

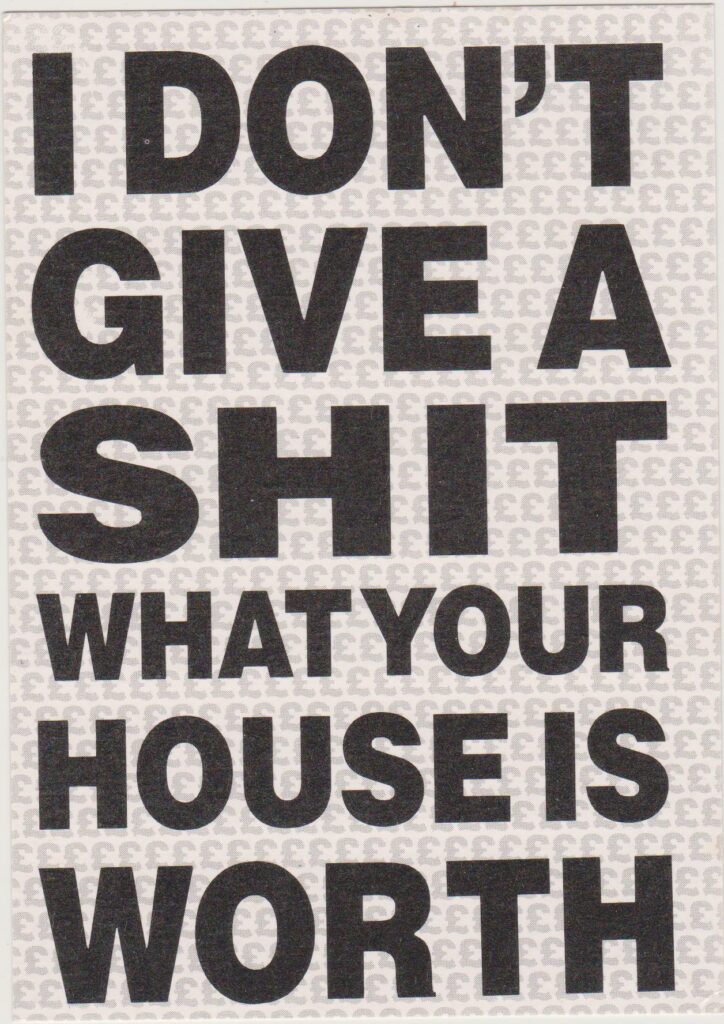

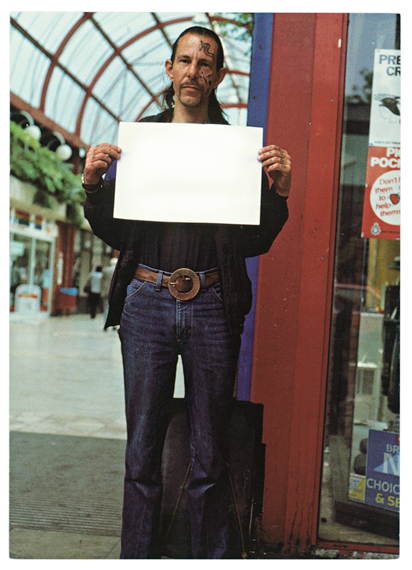

Every postcard sent by Lynn actually exists. As a way of communicating Lynn’s politics, I mostly selected on her behalf commercially printed cards from the political section of my collection, which is in the process of preparation for a substantial exhibition planned for Tate Liverpool. Some of these postcards, particularly the outstanding body of work published by Leeds Postcards between 1979 and 1996, were printed in relatively large numbers and, being easy enough to find, appear in several of my exhibitions. Paul Morton’s great Thatcher card [p.42] and Richard Scott’s graphic I Don’t Give A Shit What Your House Is Worth [p.15] were both illustrated in the catalogue which Thames & Hudson published of my British Museum show The World Exists to be Put on a Postcard. Spare examples of these two Leeds Postcards will also go to Liverpool. Another show I am working on, of artists’ portrait postcards, is planned for the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and will include a rare postcard image of the avant-garde American performer Vito Acconci [p.118] – he is one of Lynn’s ‘favourite artists’, and one of mine too. Already fixed for 2023/24 is an exhibition of European artists’ postcards at the Dresden Kupferstich Kabinett, of the same size and scope as the British Museum show, resulting in the permanent gift by me to Dresden of another thousand cards, including the artist Carla Cruz’s postcard To be an Artist in Portugal is an Act of Faith [p.245].

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

***