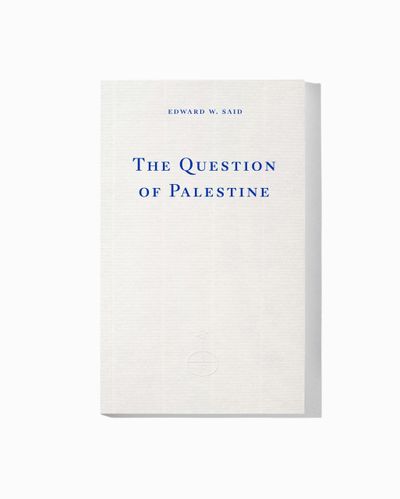

A major work by one of the great public intellectuals of the twentieth century, The Question of Palestine was the first book to narrate the modern Palestinian experience in English. Edward Said’s project to ‘bring Palestine into history’ was unquestionably a success – there is no longer a question of whether Palestine had a history before colonization – and yet Palestinian self-determination is as distant as ever. With the rigorous scholarship he brought to his influential Orientalism and shaped by his own life in exile in New York, Said’s account of the traumatic national encounter of the Palestinian people with Zionism is still as pertinent and incisive today as it was on first publication in 1979.

The Question of Palestine

Preface by Saree Makdisi

Fitzcarraldo Classic No.7 | French paperback with flaps, 376 pages

Audiobook read by Peter Ganim | Published 21 November 2024

The Question of Palestine

Preface by Saree Makdisi

INTRODUCTION

Although most of this book was written during 1977 and the early part of 1978, its frame of reference is by no means confined to that very important period in modern Near Eastern history. On the contrary, my aim has been to write a book putting before the Western reader a broadly representative Palestinian position, something not very well known and certainly not well appreciated even now, when there is so much talk of the Palestinians and of the Palestinian problem. In formulating this position, I have relied mainly on what I think can justly be called the Palestinian experience, which to all intents and purposes became a self-conscious experience when the first wave of Zionist colonialists reached the shores of Palestine in the early 1880s. Thereafter, Palestinian history takes a course peculiar to it, and quite different from Arab history. There are, of course, many connections between what Palestinians did and what other Arabs did in this century, but the defining characteristic of Palestinian history—its traumatic national encounter with Zionis —is unique to the region.

This uniqueness has guided both my aim and my performance (however flawed both may be) in this book. As a Palestinian myself, I have always tried to be aware of our weaknesses and failings as a people. By some standards we are perhaps an unexceptional people; our national history testifies to failing contest with a basically European and ambitious ideology (as well as practice); we have been unable to interest the West very much in the justice of our cause. Nevertheless we have begun, I think, to construct a political identity and will of our own; we have developed a remarkable resilience and an even more remarkable national resurgence; we have gained the support of all the peoples of the Third World; above all, despite the fact that we are geographically dispersed and fragmented, despite the fact that we are without a territory of our own, we have been united as a people largely because the Palestinian idea (which we have articulated out of our own experience of dispossession and exclusionary oppression) has a coherence to which we have all responded with positive enthusiasm. It is the full spectrum of Palestinian failure and subsequent return in their lived details that I have tried to describe in this book.

Yet I suppose that to many of my readers the Palestinian problem immediately calls forth the idea of “terrorism,” and it is partly because of this invidious association that I do not spend much time on terrorism in this book. To have done so would have been to argue defensively, either by saying that such as it has been our “terrorism” is justified, or by taking the position that there is no such thing as Palestinian terrorism as such. The facts are considerably more complex, however, and some of them at least bear some rehearsal here. In sheer numerical terms, in brute numbers of bodies and property destroyed, there is absolutely nothing to compare between what Zionism has done to Palestinians and what, in retaliation, Palestinians have done to Zionists. The almost constant Israeli assault on Palestinian civilian refugee camps in Lebanon and Jordan for the last twenty years is only one index of these completely asymmetrical records of destruction. What is much worse, in my opinion, is the hypocrisy of Western (and certainly liberal Zionist) journalism and intellectual discourse, which have barely had anything to say about Zionist terror. Could anything be less honest than the rhetoric of outrage used in reporting “Arab” terror against “Israeli civilians” or “towns” and “villages” or “schoolchildren,” and the rhetoric of neutrality employed to describe “Israeli” attacks against “Palestinian positions,” by which no one could know that Palestinian refugee camps in South Lebanon are being named? (I quote now from reports of recent incidents during late December 1978.) Since 1967, with Israel in occupation of the West Bank and Gaza, there has been no letup in the daily outrage of Israeli occupation, and yet nothing galvanizes the Western press (and the Israeli information media) as much as a bomb in a Jerusalem market. With sentiments bordering on pure disgust, I must note here that not a single U.S. newspaper carried the following interview with General Gur, Chief of Staff of the Israeli Army:

Q—Is it true [during the March 1978 Israeli invasion of Lebanon] that you bombarded agglomerations [of people] without distinction?

A—I am not one of those people who have a selective memory. Do you think that I pretend not to know what we have done all these years? What did we do the entire length of the Suez Canal? A million and a half refugees! Really: where do you live? … We bombarded Ismailia, Suez, Port Said, and Port Fuad. A million and a half refugees … Since when has the population of South Lebanon become so sacred? They knew perfectly well what the terrorists were doing. After the massacre at Avivim, I had four villages in South Lebanon bombed without authorization.

Q—Without making distinctions between civilians and noncivilians?

A—What distinction? What had the inhabitants of Irbid [a large town in northern Jordan, principally Palestinian in population] done to deserve bombing by us?

Q—But military communiqués always spoke of returning fire and of counterstrikes against terrorist objectives.

A—Please be serious. Did you not know that the entire valley of the Jordan had been emptied of its inhabitants as a result of the war of attrition?

Q—Then you claim that the population ought to be punished?

A—Of course, and I have never had any doubt about that. When I authorized Yanouch [diminutive name of the commander of the northern front, responsible for the Lebanese operation] to use aviation, artillery and tanks [in the invasion], I knew exactly what I was doing. It has now been thirty years, from the time of our Independence War until now, that we have been fighting against the civilian [Arab] population which inhabited the villages and towns, and every time that we do it, the same question gets asked: should we or should we not strike at civilians? [Al-Hamishmar, May 10, 1978]

(…)

‘This reissue of The Question of Palestine only lends more weight and value to Edward Said’s work, to his vision and analysis, to the enduring need for his core principles of justice and empathy. Principles that have perhaps never been as severely tested as they are today. Passionate and patient, the book displays all the features that made Said a great thinker and a powerful advocate, whose absence continues to be felt.’

— Ahdaf Soueif, author of The Map of Love

‘In this seminal text, Edward W. Said stridently diagnoses western hypocrisy and makes the case for Palestinian liberation, paving the way for so many thinkers who came after him. I wish it were not so, but The Question of Palestine is just as relevant now as it was in 1979.’

— Isabella Hammad, author of Enter Ghost

‘Edward Said is among the truly important intellectuals of our century.’

— Nadine Gordimer

‘When Edward Said died in September 2003, after a decade-long battle against leukemia, he was probably the best-known intellectual in the world…. Over three decades, virtually single-handedly, he wedged open a conversation in America about Israel, Palestine and the Palestinians. In so doing he performed an inestimable public service at considerable personal risk.’

— Tony Judt

‘[A]rguably New York’s most famous public intellectual after Hannah Arendt and Susan Sontag, and America’s most prominent advocate for Palestinian rights.’

— Pankaj Mishra, New Yorker

Edward W. Said (1935–2003) was one of the world’s most influential literary and cultural critics. Professor of English and Comparative Literature at Columbia University, he was the author of twenty-two books, including Orientalism, Culture and Imperialism and Out of Place. He was also a music critic, opera scholar, pianist and the most eloquent spokesman for the Palestinian cause in the West.

Saree Makdisi teaches English literature at UCLA. His most recent book is Tolerance Is a Wasteland: Palestine and the Culture of Denial.