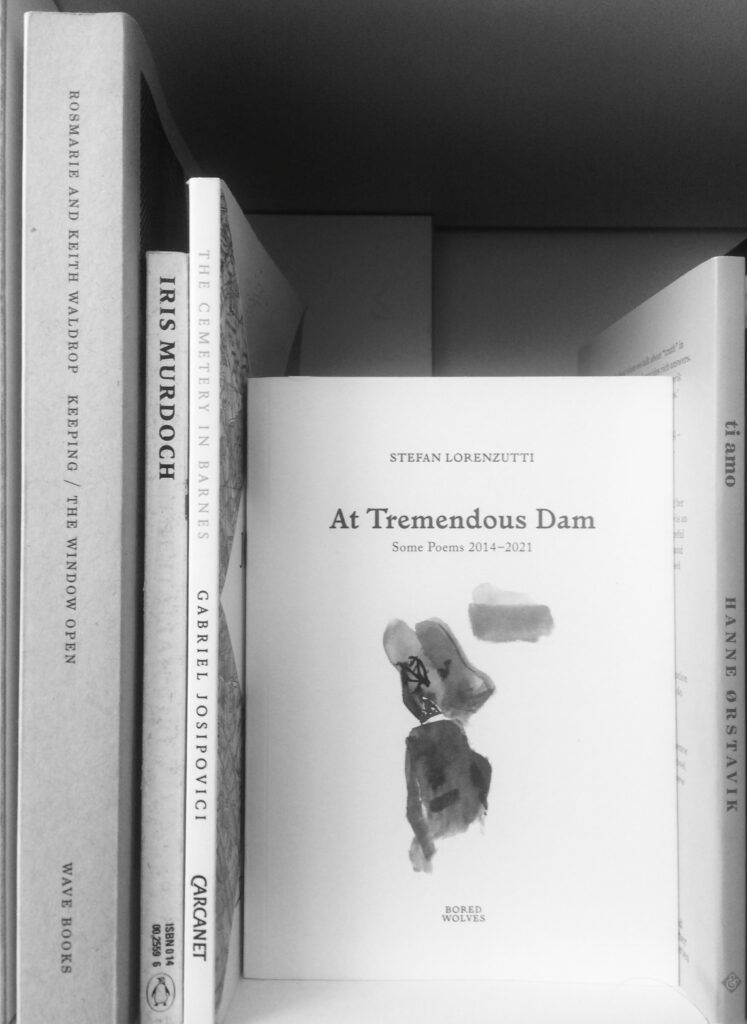

Keeping / the window open: Interviews, statements, alarms, excursions by Rosmarie and Keith Waldrop, edited by Ben Lerner (Wave Books, 2019)

I bought this as a present to myself for my birthday a month or so ago. I wanted to learn more about the Waldrop’s publishing project: how they co-founded Burning Deck in 1961, a flexible structure for experimental poetry and prose, then kept it alive – publishing pamphlets for the next fifty-six years. Keeping / the window open is fascinating and instructive on small-scale editing and publishing. But it’s also a vital archive of work on translating, critical writing, poetry, prose, prose poetry, the line, the novel, and the inter-relations between all the above. I am nowhere near reading through all of it. But there is one line I’ve already copied out and pasted above my desk: something Keith says in an interview. I read it and found in it a new kind of permission: ‘…you don’t have to decide whether you’re going to “think” or “feel”’. It was amazing to read that stated so directly and so simply. He goes on, completing the thought: “‘…you don’t have to decide whether you’re going to “think” or “feel”, to use high diction or low diction, or whatever. I mean you can combine these things – any things – if you can do it (it’s a problem of form).’

The Italian Girl by Iris Murdoch (Penguin, 1964)

I recently bought this second-hand, hence the sun-faded spine: one of the few remaining Murdoch novels I hadn’t read. As is in all her books, in The Italian Girl, there’s a collection of characters placed in their starting positions, each one located and to some extent defined by the power they seem to hold or don’t hold over the others. Edmund, the novel’s focus, is returning home for his mother’s funeral (the book has this amazing sub-title: ‘A Dazzling Tale of Love For Mother.’ ) At first slowly, then more dramatically, new alliances form and break down, characters are contrasted then bound together, and everyone starts to move. By the end, what’s taken place is this totally unforeseen, transformative rearrangement. I love many things about Murdoch’s novels, among them how all her characters think. About how to live among other people, how to exist as their own complicated selves, how to see others clearly: as complex, thinking-feeling people in their own right. For Murdoch, these big ethical and political questions are never the reserve of the educated or the leisured classes: as in real-life, they concern everyone, animals included. But even if I weren’t into this aspect of her work, I’d recommend The Italian Girl for its description of Otto – Edmund’s physically huge elder brother — eating great fistfuls of ‘herbage’ grabbed in from the garden, mint and marjoram mixed with grass and groundsel. Like a cow, or an elephant.

The Cemetery in Barnes by Gabriel Josipovici (Carcanet, 2018)

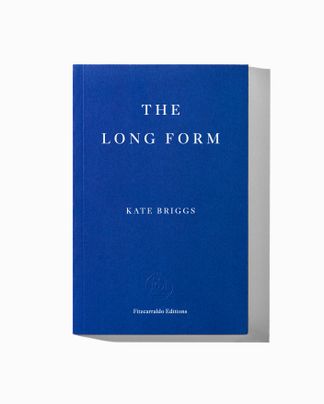

The Cemetery in Barnes was shortlisted for The Goldsmiths’ Prize the year it was published. Josipovici is among the living writers whose innovations in prose I think about most. I kept this short novel, along with the earlier, sparer, Everything Passes (2006), and the even earlier Contre-Jour (1998) within reach over the past few years. What fascinates me about these books is how they treat the novel spatially — as a composition which of course must run forward in time, but can also open sideways, forming parallel tracks. The Cemetery in Barnes seems almost to fold back onto itself or into itself through its use of refrain. We listen to very different kinds of music – the three of voices of the novel repeat the structure of an opera by Monteverdi. In contrast, the writing of The Long Form was informed by Whitney Houston’s ‘My Love is Your Love’, which may or not may not sound unlikely, depending on your tastes. But is nevertheless true: I listened to the track endlessly. Not for the sentiment of the song, exactly, but for the bounce and carry of the bass. For the way the lyrics get handed back and forth over the top of it. Venturing something. Then passing it back, only now with a slight modification, a small shift in emphasis. This for me is Josipovici territory, and possibly what grounds his long-term interest in translation — The Cemetery in Barnes is about a translator who moves from to London to Paris and then to Wales. The characters like the narration keep falling back into repetition – but every re-saying of what has already been said the novel releases something new.

At Tremendous Dam: Some Poems 2014-2021 by Stefan Lorenzutti (Bored Wolves, 2021)

Bored Wolves is a great, contrary name for a wholly unbored and unboring small press. This collection is by its co-founder, Stefan Lorenzutti, who runs the press with his partner Joanna Osiewicz-Lorenzutti, out of ‘Kraków and the Polish Highlands.’ I discovered their work thanks to two former students who recently published their own first collections with Bored Wolves (Sweaty Leaves by Petter Dahlstrom Persson and Bundle by Linus Bonduelle with drawings by Pommelien Koolen). The books are always visually interesting – a feature part explained by the fact that they tend to publish poets with their own parallel image-making practices, as well as new collaborations with artists. Lorenzutti’s poems share the some of the qualities I’ve come to associate with his lively, unpredictable list: an attentiveness to the intense colours, atmospheric conditions, textures and materials of everyday life; strange new precisions that give way to humour then unexpected sites of vulnerability. These are poems that make life feel weird, abundant; basically unfathomable but definitely worth living.

ti amo by Hanne Ørstavik, translated by Martin Aitken (And Other Stories, 2022)

I received this slim book as part of my subscription to The Republic of Consciousness – from whom I receive a new book by a different small press (in the UK and Ireland) each month. Ørstavik’s ti amo arrived at the start of the year. I read the backcover and immediately put it away on the shelf. Thinking: a novel about someone else’s loss, or rather preparation for loss, and for grief, is truly the opposite of what I want to read right now. But then a close friend read it, and she found it extraordinary. She gently suggested that I might find something in it, too. She was right: from the very first page, the first sentence, there’s this honesty of voice. A voice weighted with dread and waiting but also shaky with love and wonder. The novel is described on the back as ‘very hard and very beautiful.’ It is very hard. But, somehow, without this being in any way tritely or easily achieved, it is also very beautiful. A magnificent translation of a life-companion of a book.