Vincenzo Latronico, author of Perfection, tr. Sophie Hughes, published 13 February 2025, shares his list of cultural primers that inspired the writing of his novel.

ALBUMS

76:14 by Global Communication (1994) and Blink a Few Times to Clear Your Eyes by Grand River (2020)

I tend to be a bit embarrassed when talking about my music tastes because they tend to be very narrow. I latch onto an artist or album and for several months I end up listening to that on repeat. When I am writing it has to be instrumental music in order to avoid being distracted by words, and I always seem to perceive something of the music’s pace and soundscape in the voice of what I wrote. When writing Perfection I was listening to soft, repetitive, dreamy ambient music – Grand River’s, which had just come out, but mostly Global Communication. I think it helped me find a tone that was even yet varied, with sudden surprises and a tinge of playfulness but no grandiosity, no stark contrasts. I can still match some parts of the book to specific tracks. I guess I imprinted on this music at that time because it conveys the atmosphere I was looking for.

ESSAY

The Fall of Language in the Age of English by Minae Mizumura, tr. Mari Yoshihara and Juliet Winters Carpenter (2008)

So much of my thinking about novels has been shaped by Mizumura’s memoir/essay on the geography of power in international literature – how the hierarchy of languages shifting towards English is impacting what non-native readers expect, and what writers feel allowed to write. In many ways, Perfection started out as an attempt to solve the problem Mizumura so powerfully and clearly articulates: how can a ‘local’ author avoid being a specialized purveyor of exoticness (be it pizza and camorra in Amalfi or sushi and yakuza in Tokyo), in a culture which seems to ask but that? What common ground do peripheries have, if not the English-speaking centre? For me, a precarious and flawed yet possible answer was Berlin.

ESSAY

‘On the Inevitability of the Middle Classes: A Sociological Caprice’ from Critical Essays by Hans Magnus Enzensberger, tr. by Judith Ryan (1997)

I return often to Enzensberger’s essays since I first discovered them (I originally learned German to read his poetry), and this one is one of my favourites. Perec’s original Things ended with a quote from Karl Marx, and when Perfection was translated into German my publisher suggested I mirror that too, for symmetry. This, from Enzensberger’s ‘On the Inevitability of the Middle Classes’, is what I picked: ‘That you who are reading this are reading it is almost proof in itself: proof that you belong in it.’

NOVEL

La Séparation by Dan Franck (1991)

I wasn’t aware of Franck’s 1991 book when I wrote Perfection, but when it was republished in Italian I was shocked to see how successfully he had rewritten Perec’s Things to adapt it to a completely different situation – turning inward his obsession with describing the surface of things, treating a divorce as if it were a prized piece of real estate. It is a little gem of a book, and further proves how fertile and malleable Perec’s original intuition was to begin with.

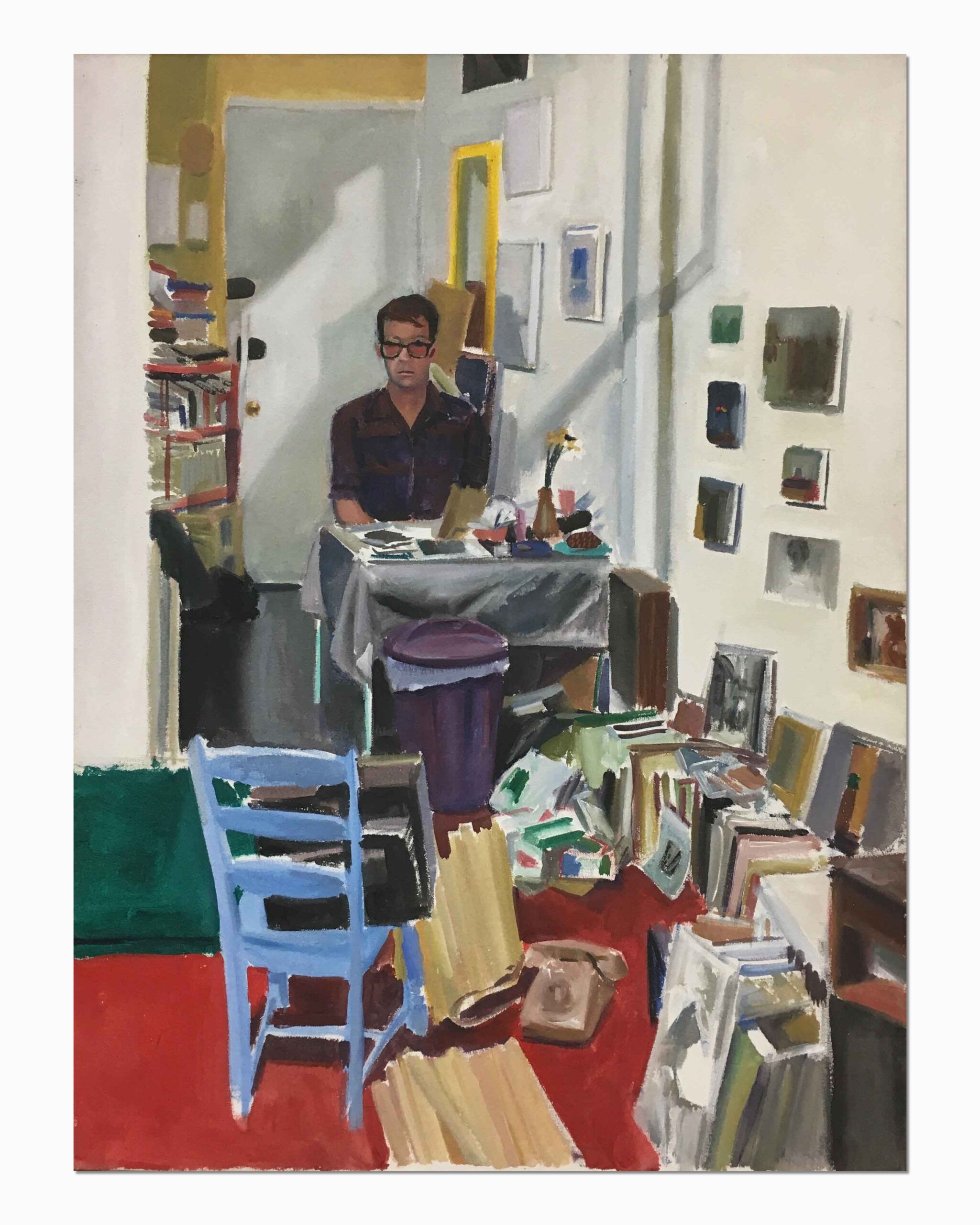

PAINTING

Stuart at Home by Patrick Angus (1986)

At the time of writing Perfection, and in general ever since, I have been deeply fascinated by Patrick Angus’ paintings of interiors. I am aware I am on some level deliberately misreading his art – which focused on the gay community in 1980s New York, an incredibly delicate and touching representation of queer love and desire so far from its codified canons. What keeps striking me in his portraits is how he refused any hierarchy between figure and background. He was clearly fascinated with interior details – furniture, crockery, plants – and the men he depicted blended into them like animals hiding in their habitat. And yet they did not hide – on the contrary, Angus seemed to suggest those rooms revealed as much about his subjects as their pose and traits, maybe even more. They were part of the portraits in the fullest sense. I would like to think I tried to do the same when depicting my characters. There are many such paintings – I’d wish to include more – this is Stuart at Home, 1986.

NOVEL

Things: A Story of the Sixties by Georges Perec, tr. Helen Lane (1965)

Perfection started out as a rewriting of George Perec’s Things: A Story of the Sixties. The parallel between the two texts is extremely strong at the beginning but loosens out over the course of the book; still, the inspiration is visible throughout my whole novel, in filigree. The use of description as the main narrative tool; the confinement of plot to the background while foregrounding what usually is just ‘setting’; the dispassionate chronicling of inner lives as if they were items in a product catalogue: it all comes from there. Initially, I was surprised realizing how a narrative strategy devised to capture a typically twentieth century phenomenon – consumerism, as spurred by the rise of TV and mass magazines – could adapt so pliably to a wholly transformed world – the digital one I write about. But ultimately I understood both novels deal with a revolution in media, to tell the story of the last generation to come of age before the divide: making them overeager early-adopters, lost in a landscape they didn’t grow up in.

NOVEL

Wilful Disregard by Lena Andersson, tr. Sarah Death (2015)

This is the novel I was reading when I took up writing Perfection for good – I’d started a year before, then the pandemic happened and it took about a year for it not to seem too frivolous (at times it still does). Andersson does something masterful – in some ways close to what Franck did: she finds a way to dispassionately describe the narrator’s inner landscape from within, with a clinical eye that generates a kind of estrangement. It is a love story in which the love plot per se matters not at all, a narrative case study in self-delusion. I think I learned (copied?) a lot from it. The English translation is different, but the one I read opens, memorably, like this: ‘Ester Nilsson was a person.‘