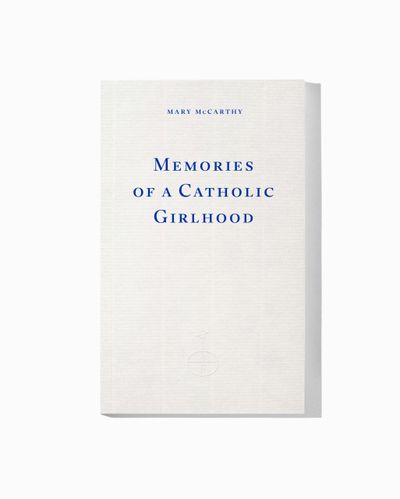

Blending memories and family myths, Mary McCarthy takes us back to the 1920s, when she was orphaned into a world of relations as colourful, potent and mysterious as the Catholic religion. There was her Catholic grandmother who combined piousness with pugnacity, and her veiled Jewish grandmother who mourned the disastrous effects of a face-lift; there was wicked Uncle Myers who beat her for the good of her soul, and Aunt Margaret who laced her orange juice with castor oil, and taped her lips at night to prevent unhealthy ‘mouth-breathing’. ‘Many a time in the course of doing these memoirs,’ Mary McCarthy says, ‘I have wished that I were writing fiction.’ But these were the people, along with the Ladies of the Sacred Heart convent school, who inspired her engaging perception, her devastating sense of the sublime and ridiculous, and her witty, novelist’s imagination. Memories of a Catholic Girlhood is a major work by one of the leading American intellectuals of the twentieth century – witty, scathing, piercingly insightful and stylishly written.

Memories of a Catholic Girlhood

Introduction by Colm Tóibín

Fitzcarraldo Classic No.8 | French paperback with flaps, 264 pages

Published 13 March 2025

Memories of a Catholic Girlhood

Introduction by Colm Tóibín

o

To The Reader

These memories of mine have been collected slowly, over a period of years. Some readers, finding them in a magazine, have taken them for stories. The assumption that I have ‘made them up’ is surprisingly prevalent, even among people who know me. ‘That Jewish grandmother of yours …!’ Jewish friends have chided me, sceptically, as though to say, ‘Come now, you don’t expect us to believe that your grandmother was really Jewish.’ Indeed she was, and indeed I really had a wicked uncle who used to beat me, though more than once, after some public appearance, I have had a smiling stranger invite me to confess that ‘Uncle Myers’ was a hoax. I do not understand the reason for these doubts; I have read about far worse men than my cruel uncle in the newspapers, and many Gentile families possess a Jewish ancestor. Can it be that the public takes for granted that anything written by a professional writer is eo ipso untrue? The professional writer is looked on perhaps as a ‘story-teller’, like a child who has fallen into that habit and is mechanically chidden by his parents even when he protests that this time he is telling the truth.

Many a time, in the course of doing these memoirs, I have wished that I were writing fiction. The temptation to invent has been very strong, particularly where recollection is hazy and I remember the substance of an event but not the details – the colour of a dress, the pattern of a carpet, the placing of a picture. Sometimes I have yielded, as in the case of the conversations. My memory is good, but obviously I cannot recall whole passages of dialogue that took place years ago. Only a few single sentences stand out: ‘They’d make you toe the chalk line,’ ‘Perseverance wins the crown,’ ‘My child, you must have faith.’ The conversations, as given, are mostly fictional. Quotation marks indicate that a conversation to this general effect took place, but I do not vouch for the exact words or the exact order of the speeches.

Then there are cases where I am not sure myself whether I am making something up. I think I remember but I am not positive. I wonder, for instance, whether the Mesdames of the Sacred Heart convent really talked as much about Voltaire as I have represented them as doing; all I am sure of is that I first heard of Voltaire from the nuns in the convent. And did they really speak to us of Baudelaire? It seems to me now extremely doubtful, and yet I wrote that they did. I think I must have thrown Baudelaire in for good measure, to give the reader an idea of the kind of poet they exalted while deploring his way of life. The rumour in the convent was that our nuns had a special dispensation to read works on the Index, and that was how we liked to think of them, cool and learned, with their noses in heretical books. When I say ‘we’, however, perhaps I mean only myself and a few other ‘original’ spirits.

I have not given the right names of my teachers or of my fellow-students, in the convent and later in boarding school. But all these people are real, they are not composite portraits. In the case of my near relations, I have given real names, and, wherever possible, I have done this with neighbours, servants, and friends of the family, for, to me, this record lays a claim to being historical – that is, much of it can be checked. If there is more fiction in it than I know, I should like to be set right; in some instances, which I shall call attention to later, my memory has already been corrected.

One great handicap to this task of recalling has been the fact of being an orphan. The chain of recollection – the collective memory of a family – has been broken. It is our parents, normally, who not only teach us our family history but who set us straight on our own childhood recollections, telling us that this cannot have happened the way we think it did and that that, on the other hand, did occur, just as we remember it, in such and such a summer when So-and-So was our nurse. My own son, Reuel, for instance, used to be convinced that Mussolini had been thrown off a bus in North Truro, on Cape Cod, during the war. This memory goes back to one morning in 1943 when, as a young child, he was waiting with his father and me beside the road in Wellfleet to put a departing guest on the bus to Hyannis. The bus came through, and the bus driver leaned down to shout the latest piece of news: ‘They’ve thrown Mussolini out.’ Today, Reuel knows that Mussolini was never ejected from a Massachusetts bus, and he also knows how he got that impression. But if his father and I had died the following year, he would have been left with a clear recollection of something that everyone would have assured him was an historical impossibility, and with no way of reconciling his stubborn memory to the stubborn facts on record.

As an orphan, I was brought up between two sets of grandparents, all of whom are now dead, beyond questioning, and who knew very little, in any case, of the daily facts of our childhood, either before or after the death of our parents. My aunts and uncles, too, were remote from our family life and took small interest in it, my brother Kevin, whose memory corroborates mine for the period of our stay in Minneapolis, was too young when my parents died to remember much about them. For events of my early childhood I have had to depend on my own sometimes blurry recollections, on the vague and contradictory testimony of uncles and aunts, on a few idle remarks of my grandmother’s, made before she became senile, and on some letters written me by a girlhood friend of my mother’s. For the Minneapolis period, I have had the help of Kevin, but for later events, in Seattle, when my brothers and I were separated, I am reduced again, chiefly to my own memory. What more ancient family history I know has been pieced together from hearsay, from newspaper clippings, old photographs, and a sort of scrapbook journal kept by my great-grandfather, who lived to be ninety-nine. This old man seems to have been the only member of the family who was alive to the interest of history. The grandmother I was closest to, his daughter-in-law (as I will show later), disliked talking about the past.

Yet the very difficulties in the way have provided an incentive. As orphans, my brother Kevin and I have a burning interest in our past, which we try to reconstruct together, like two amateur archaeologists, falling on any new scrap of evidence, trying to fit it in, questioning our relations, belabouring our own memories. It has been a kind of quest, in which Kevin’s wife and my husband and even friends have joined, poring over albums with us, offering conjectures: ‘Do you think your grandmother could have been jealous of you?’ ‘Could your grandfather have had a nervous breakdown?’

(…)

‘It could be argued that [McCarthy’s] finest book is Memories of a Catholic Girlhood, first published in 1957 and now reissued in a handsome paperback by Fitzcarraldo Editions…. Colm Tóibín, in his sympathetic and subtle introduction, notes the similarities between Mary McCarthy and the poet Elizabeth Bishop, both of whom grew up parentless, and used their orphanhood as literary material. Yet the biographies of both women bespeak an incurable sadness and a sense of damage, however bravely borne. McCarthy was the sprightlier and more feisty of the two, and in Memories of a Catholic Girlhood she made a small, or perhaps more than small, masterpiece.’

— John Banville, Observer

‘McCarthy has integrity, writes what she wants and keeps you with her all the way. The end notes following each chapter let McCarthy play a confident game of truth-twisting, flagging her narrative inventions without so much as the whiff of an apology…. I fear McCarthy would be disappointed in me for giving an unqualified rave review, my critical faculties seduced by her rakish pen…. As a ruthlessly honest interrogation of family dynamics, as an account of a 1920s Irish-American life before it became fashionable, and as a portrait of an intellectual awakening – this memoir stands as a classic.’

— Naoise Dolan, Irish Times

‘Admission of changed names and hazarded dialogue is now common practice in memoir but, as the novelist Colm Tóibín describes in his introduction to this smart new edition, McCarthy is after more than just the trust of her reader. She set herself free with these well-integrated addenda, gave herself permission to write “scenes and characters that were more memorable than adherence to any set of full facts might demand”. And the tactic works. A big part of the book’s charm is its self-consciousness…. Few writers have captured so precisely what it means to be the kind of resolute child who believes forcefully and dutifully in whatever it is they happen to be convinced by that day. This is a book worthy of its label: a true classic.’

— Ceci Browning, Sunday Times

‘Read on its own, this book is a powerful testament to the human spirit’s capacity for reinvention. McCarthy’s direct style, confessional in tone, has the feel of a friend whispering secrets into your ear. The prose is wry and colourful and never less than captivating, whether the reader is wincing at her aunt’s cruelties or shuddering at McCarthy’s teenage misadventures.… Read alongside McCarthy’s other work, which includes several volumes of criticism, essays and journalism (she reported from North and South Vietnam), Memories adds welcome flesh to the autobiographical scaffolding of her eight novels.’

— Susie Mesure, Prospect Magazine

‘First Lady of American Letters … our Joan of Arc.’

— Norman Mailer

‘When my friends and I were in our twenties in the 1950s, we read two writers – Colette and Mary McCarthy – as others read the Bible: to learn better who we were and how, given the constraint of our condition, we were to live.’

— Vivian Gornick

’Published in 1957, Memories of a Catholic Girlhood … is considered by some to be the best of her two dozen books, including eight novels and several volumes of essays, reportage and criticism. Its superiority derives not only from the passionate sense of justice that imbues the depiction of her ghastly Cinderella childhood, but also the singular circumstances of its composition.’

— J. Michael Lennon, Times Literary Supplement

‘Superb… so heartbreaking that in comparison Jane Eyre seems to have got off lightly.’

— Anita Brookner, Spectator

‘Brilliant.’

— Penelope Lively, Telegraph

Mary McCarthy (1912–1989) was a novelist, essayist and critic. Her political and social commentary, literary essays and theatre criticism appeared in magazines such as Partisan Review, the New Yorker, Harper’s and the New York Review of Books. She was the author of numerous novels, including The Group (1963), three works of autobiography and two travel books about Italy.

Colm Tóibín is the author of eleven novels, including The Master, Brooklyn and The Magician, and two collections of stories. He has been three times shortlisted for the Booker Prize. In 2021, he was awarded the David Cohen Prize for Literature. He is Irene and Sidney B. Professor of the Humanities at Columbia University.