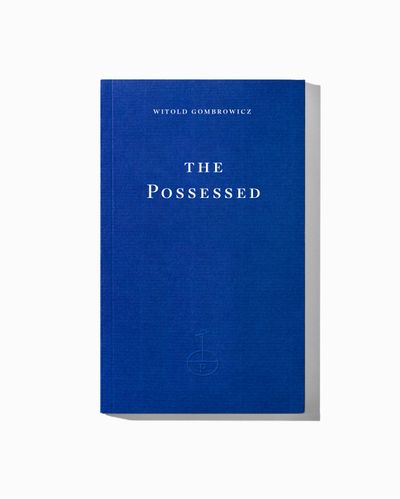

In The Possessed, Witold Gombrowicz, considered by many to be Poland’s greatest modernist, draws together the familiar tropes of the Gothic novel to produce a darkly funny and playful subversion of the form. With dreams of escaping his small-town existence and the limitations of his status, a young tennis coach travels to the heart of the Polish countryside where he is to train Maja Ochołowska, a beautiful and promising player whose bourgeois family has fallen upon difficult circumstances. But no sooner has he arrived than the relationship with his pupil develops into one of twisted love and hate, and he becomes embroiled in the fantastic happenings taking place at the dilapidated castle nearby. Haunted kitchens, bewitched towels, conniving secretaries and famous clairvoyants all conspire to determine the fate of the young lovers and the mad prince residing in the castle. Translated directly into English for the first time by Antonia Lloyd-Jones, The Possessed is a comic masterpiece that, despite being a literary pastiche, has all the hallmarks of Gombrowicz’s typically provocative style.

The Possessed

Translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones, with an introduction by Adam Thirlwell

Fitzcarraldo Classic No.3 | French paperback with flaps, 416 pages

Published 18 October 2023

The Possessed

Translated by Antonia Lloyd-Jones, with an introduction by Adam Thirlwell

‘Can’t you see there’s a sign here that says “Do not lean out”? Do official orders mean nothing to you?

This remark was addressed to the young man leaning out of the window by a faded, elderly man in pince-nez. It happened on a train, somewhere beyond Lublin. The young man drew his head inside and turned around.

‘Do you know what the next stop is?’ he asked.

If I inquire of you whether you are aware that leaning out of the window while the train is in motion is not allowed, perhaps it would be appropriate to answer the question in the first place, and only then pose one of your own,’ said the stickler for form with the face of a fish, bristly hair, and a gold watch chain hanging in the region of his belly. The young man instantly replied in a free and frivolous tone: ‘Oh, sorry.

This freedom and frivolity increased the fish-faced gentleman’s irritation. Councillor Szymczyk was inordinately fond of lecturing and drilling others, but he couldn’t tolerate his remarks not being taken seriously enough. He cast his victim a look of disgust.

This was a dark blond of about twenty, with an extremely neat physique. Although the summer was coming to an end and the evenings could be cool, he was only wearing a blue, sleeveless string top, grey trousers and tennis shoes on his bare feet.

Who might this be? thought the councillor. He’s got two rackets, so perhaps he’s the son of a resident of these parts? But his hands are rough, with poorly kept nails, as from physical work. Anyway, his hair is not well groomed and his voice is rather common. A proletarian, then? No, a proletarian wouldn’t have ears and eyes like his. But then the mouth and chin are almost working class… and altogether there’s something suspicious about him… a sort of hybrid.

The other passengers must have shared his opinion, because they too were glancing furtively at the young man, who stood leaning against the wall. Finally Councillor Szymczyk became so curious that he decided for the time being to drop further polemic on the topic of failing to attend seriously to instructions and advice given him by qualified people. He proceeded to establish the stranger’s personal details, which in any case came to him easily, as even when on holiday he always considered himself an official, accustomed to filling in the blanks on forms.

‘What is your employment?’ he asked.

‘I’m a tennis coach.’

‘Age?’

‘Twenty.’

‘Twenty? Twenty what? Twenty years old? Please answer properly!’ he said, with impatience and irritation.

‘Twenty years old.’

‘And where are you going?’ asked the councillor suspiciously. He liked this character less and less. He always felt a certain suspicion towards persons who answered questions too hastily and compliantly; many years of office experience had taught him that as a rule such individuals either already had, or intended to have, something on their conscience…

‘I’m going to a place near here,’ the boy replied, ‘to an estate where I’ve been hired as a coach.’

‘Ah,’ exclaimed the councillor, ‘then perhaps you are going to Połyka, to the Ochołowskis? Eh? Of course! I guessed at once, since Miss Ochołowska is by all accounts an accomplished tennis player, sir. Are you there for long?’

‘Nooo… Or rather I don’t know how it will turn out. I’m to repair the rackets, refresh the court and practise with the young lady, as apparently she has no one to play against.’

‘I’m going there too,’ the councillor felt it appropriate to reveal, then stretched out a hand and said abstractedly: ‘Szymczyk.’

To which the coach replied with a bow and said: ‘Walczak.’

At this point they were approached by a hearty old man who had been listening closely to their conversation from the start. ‘What, are you gentlemen going to Połyka?’ he exclaimed. ‘This is splendid, for I am going there too. Allow me to introduce myself,’ he said, addressing the councillor. ‘I am Skoliński, Czesław, professor, or, to be precise, art historian. Skoliński! You must be going to the boarding house, eh? I can assure you that you’ve struck gold – the manor at Połyka is paradise, sir, not a boarding house! Sometimes I really am pleased that the landed gentry is going bust and must establish boarding houses at their manors, for nowhere does one get as good a rest as in the countryside. I’ve been staying there for a fortnight now, I’ve been up to Warsaw for a while, but now I’m on my way back again. It’s a superb place, gentlemen! À propos, Miss Maja Ochołowska, your future partner,’he boomed at the young coach, ‘is also travelling on this train. Skoliński, if you please, professor, or, to be precise, art historian. I’d introduce you to her, gentlemen, but I do not wish to be indiscreet, because she is travelling with her fiancé… That’s to say, her fiancé is travelling with Prince Holszański – you know, the prince from Mysłocz, which is next door to Połyka – so her fiancé, Mr Cholawicki, is travelling in one compartment with the prince, whose secretary he is, while she, poor lass, is in the next compartment down. The prince is a little… like that…’ – he put a finger to his forehead – ‘and his secretary cannot abandon him. But in any case, we’d better not disturb the young couple.’

The train sped on, swaying steadily, through the mournful land, flat and dark-green against the setting sun. More and more often the woods crept up on either side, more and more often the train sheared through a small pine copse. The two gentlemen immersed themselves in conversation, while Marian Walczak, coach for the Zespół club in Lublin, whistled a tune as he gazed at the passing landscape. He was bored. Altogether he was often bored. Sometimes such colossal boredom came over him that he found it simply unbearable. He set off on a walk down the train.

(…)

‘Brimming with unruly, high-octane prose, the book has the hallmarks of a classic gothic story: a haunted castle, a mad prince and his conniving secretary — and, of course, treasure. At first glance, this surface is rather depthless, but look closer and you’ll see the philosophically minded Gombrowicz getting on with what he described as the central aim of his writing: “to forge a path through the Unreal to Reality”.’

— Matt Janney, Financial Times

‘[T]he ultimate tennis match is between the creaking horror of the gothic novel and the other book that haunts The Possessed: a delightfully slippery, devious work of modernism.’

— Francesca Peacock, Spectator

‘By hewing closer to the Polish without sacrificing readability, Lloyd-Jones reproduces the uncanny effect of the original, evident even in small touches…. Like the peasant left alone in the room after Maja and Marian make their escape, we cannot help but feel that we “have been here before” with Witold Gombrowicz, but never quite like this. The journey is worth taking.’

— Boris Drayluk, Times Literary Supplement

‘[T]he book has been translated for the first time directly, and sonorously, into English by Antonia Lloyd-Jones, one of the foremost interpreters of Polish literature. The “good bad book” which Gombrowicz, who was exiled from Poland after 1939, later felt ashamed of, takes comic flight, less a curio, more a complex stunner which bears comparison not only with Poe and Dostoevsky but also Gombrowicz’s Hungarian contemporary Antal Szerb. And, as Adam Thirlwell notes in a sparkling introduction: “it also has a strange layer of ultra-modernity: the dance halls and tennis courts of 1930s Warsaw.”’

— Catherine Taylor, Irish Times

‘[A] crafty and sharp exploration of the greed, lust, and vanity that spin people out of control. Gombrowicz’s gleeful misanthropy and sense of the absurd shine through the genre trappings to create a potboiler that’s enjoyable on multiple levels. This works perfectly both as a straightforward gothic akin to Du Marier’s Rebecca and as a knowing parody.’

— Publishers Weekly, starred review

‘Lloyd-Jones’ translation crackles with choice phrases, deftly capturing Gombrowicz’s gorgeous scenic descriptions, mordant sense of humor, and evocations of lurking horror. A delightful revelation of an interbellum novel from one of the great Polish modernists.’

— Kirkus starred review

‘One of the great novelists of our century.’

— Milan Kundera

‘A master of verbal burlesque, a connoisseur of psychological blackmail, Gombrowicz is one of the profoundest of late moderns, with one of the lightest touches.’

— John Updike

‘Gombrowicz is one of the super-arguers of the twentieth century…. The relentless intelligence and energy of his observations on cultural and artistic matters, the pertinence of his challenge to Polish pieties, his bravura contentiousness, ended by making him the most influential prose writer of the past half century in his native country.’

— Susan Sontag

‘There are also novels of another genre, false novels like Gombrowicz’s, that are kinds of infernal machines.’

— Jean-Paul Sartre

‘What we have here is an unusual manifestation of a writing talent.’

— Bruno Schulz

‘Gombrowicz’s art cannot be measured with the passing of decades. It is a monument of Polish prose.’

— Czeslaw Milosz

‘Despite his anxiety about genre fiction, Gombrowicz acquits himself masterfully, moving deftly between horror, romance and crime. The web of dark motivations and interdependencies that links the characters is intricately and compellingly drawn, and the plot moves at an impressive speed…. The novel’s shifts in tone and texture are handled expertly by translator Antonia Lloyd-Jones, who shows a keen sensitively not only to the language of the period but also to the genres being parodied, the translation interlaces passages of prose worthy of Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and P. G. Wodehouse, expertly re-creating the original’s tonal palette for the anglophone reader.’

— Uilleam Blacker, Literary Review

‘This novel abounds with surreal juxtapositions: personalities blurring into one another, high-stakes games of tennis, mysterious castles…. [Its] energy and irreverence are contagious.’

— Tobias Carroll, Words Without Borders

‘This campy Gothic novel begins with a young tennis coach arriving at a rural manor to train the family’s headstrong and talented daughter. The two quickly discover that they share not only an uncanny likeness but also a deep, destructive, infuriating bond. From there, Gombrowicz unveils a plethora of genre tropes – a spooky castle, a haunted chamber, a sickly old prince with a terrible secret – while also exploring class, modernity and youth. Highly recommended post-Halloween reading.’

— Alexander Wells, Exberliner

‘In a first direct and complete translation into English, Antonia Lloyd-Jones renders the lively, humorous and enticing tone of Gombrowicz’s 1939 novel, The Possessed. The tone immerses the reader in the atmosphere of the novel, which amuses yet has a latent power to haunt.’

— Gertrude Gibbons, Review31

Witold Gombrowicz (1904–69) is one of the twentieth century’s most enduring avant-garde writers. He wrote novels, short stories, plays, and his remarkable Diary; and – after returning to Europe from Argentina in 1963 – was awarded the 1967 Prix Formentor International for Cosmos.

Antonia Lloyd-Jones has translated works by many of Poland’s leading contemporary novelists and reportage authors, as well as crime fiction, poetry and children’s books. Her translation of Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead by 2018 Nobel Prize in Literature laureate Olga Tokarczuk was shortlisted for the 2019 International Booker Prize.

Adam Thirlwell is the author of four novels. His work has been translated into thirty languages, while his awards include a Somerset Maugham Award and the EM Forster Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters; in 2018 he was made a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature.