In an unnamed coastal city home to many refugees, a mother of a displaced family searches for her child, calling her name as she wanders along the cliffside road where her daughter used to work. She searches and searches until, devoid of hope and frantic with grief, she throws herself into the sea, leaving her other children behind. Bearing witness to this suicide is another woman – on a business trip from a distant country, with a swollen belly that later gives birth to a stillborn baby. In the wake of her pain, the second woman remembers her own litany of losses – of a language, a country, an identity – when once her family fled a distant war. Weaving between both narratives and written in looping prose rich with meaning, The Singularity is an astounding study of grief, migration and motherhood from one of Sweden’s most exciting new writers.

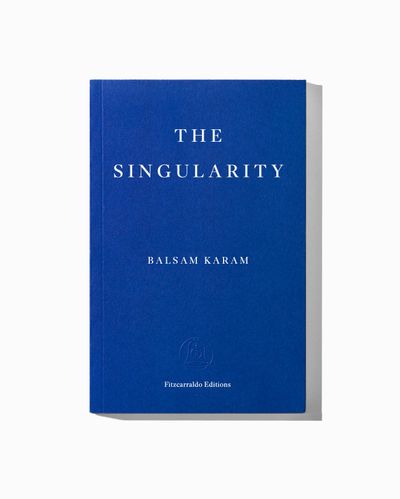

The Singularity

Translated by Saskia Vogel

French paperback with flaps, 194 pages

Published 17 January 2024

The Singularity

Translated by Saskia Vogel

PROLOGUE

¶ Meanwhile elsewhere – just as the light turns green and the cars along a coastline prepare to leave the city towards the half desert and the mountains – more slowly than ever a woman crosses the highway, which, along with the corniche, is all that holds the ocean ever rising at bay.

The woman is alone, searching for her child.

Nothing in her face recalls what once was, and if someone shouts her name, she doesn’t turn around and say no or stop it in the language no one here understands or wants anything to do with; if they stop, she doesn’t meet their gaze, and if they say, wait, she doesn’t come back with a why nor later I have just as much right to walk here as you do, why can’t you understand that?

It’s Friday and soon the city almost dissolved by the heat will fill up with tourists dressed in bright clothes and on a ramble through the food markets with fried fish and oysters. From the large galleria, the tourists as if from out of a hole will make their way to the museum quarter and the souvenir shops and afterwards, once they’ve finished shopping, move on to the rose garden, the university and the bookshops, to the corn vendor on the corner by the drooping palm groves, alone in the sun, and the cats in repose, stretching out, waiting for the heat to break and for the sun to set.

Further on – furthest on where a hill obscures the view and the road muddies in the tracks of digging machines waiting for work to begin – are also abandoned new builds made of pale concrete and steel girders and a small library where only students go.

Yes, right across the road, invisible to those at the university looking out across the green space and the faculties, stand the new builds half-finished, missing most of the walls to what could have been a living room or bedroom, a bathroom, kitchen or storeroom, and that now gaping mostly keep the students shielded from wind and rain.

At night the students roll out their bedding on the concrete and each pushes their one bag all they have left against the wall, dozes off beside it. Then they wake to the sun and the morning haze and lug their bags across the muddy earth up to their department, cast a look around. At this time of day no one but the cleaners walk the empty corridors and no cafés are open with discounted tea, coffee and yesterday’s sandwiches; none of the guards asks where you’re from or what you’re doing there and no one plants their backpack on the empty chair beside them, saying sorry this seat is taken. The students wash under their arms and between their legs in the large bathroom at one end of the corridor, then take a seat in the armchairs by the door to wait for their first seminar, falling asleep and sleeping long.

Later they’ll meet up around the fire and go over how best to make this unfinished building a home – they’ll discuss which walls are essential and from where they’ll get the sheet metal and who among them is best at construction and where they can get a hold of screws and drills. The students will talk and laugh and before bedtime open their bag and repack it, take out dry socks and a sweater and walk with their torch and books in hand up to their spot by the wall.

It’s Friday a late summer afternoon and soon the beach now vacant will have litter spread across its sun chairs and parasol stands as the ocean draws back from the rocks and reeds; the ice-cream vendors will shove their broken carts up the hill past the palms and grill kiosks, and the taxi drivers will run a rag over the seats and the cracked windshields, will wait for men in suits to wave them down and with someone beside them ask to be driven away from the corniche. Soon, the tourists – just as they for safety’s sake place a hand over their handbags and keep an eye out for the children who while waiting for work on the beach have fallen asleep sack and rake in hand – will climb the wide pavement along the twilight bright corniche and the ocean view beyond words even for those who can afford dinner and a little wine at one of the restaurants there. The tourists will take a seat and ask for sparkling water and maybe a large bottle of house wine, marinated olives with capers and garlic and salted nuts to tide them over, reclining with the late summer sea in minor revolt and the sky pitch dark and dull above the soon over-encumbered corniche.

The woman searching for her child has been there, she knows what the corniche looks like, and tonight as every other Friday night since her child disappeared she will go back there and wait; she will watch the girls, who appear out of nowhere with a mop and rag in hand, and follow them as they approach fresh spills and polish the floor to a shine once again just as the Missing One did.

She will search and look around the corniche.

Slowly endlessly tired she will wander up there – determined and clutching her bag like it’s the most valuable thing she owns, she will sit on one of the benches outside the restaurant where her child was working soon before she went missing and keep the knife warm by passing it between her hands on the corniche.

It’s the corniche she thinks of as the traffic light turns green and the shadows deeper than the day before render her invisible; it’s the corniche and the girl and the children she sees as she steps out and slowly starts making her way across the road – it’s the waiters in their black trousers black shoes and the men with their glasses of beer who stop to shout as the children walk by.

Like any other day she means to continue to the square – to the razed lot they call the alley, and on to the place where the greengrocer is already stacking melons, stone fruit and the coriander the Missing One always wanted to bring home – but she can no longer move, is stock-still in the middle of the road.

Today the world feels different somehow new and if she squeezes her wounds round and open, it doesn’t matter if the pus seeps out yellow thick and if she loses her headscarf at the roadside where she in her tiredness has lain down to sleep, it doesn’t matter if she gets it back – the air is both replete and empty and just as the woman perceives this she also senses the Missing One’s presence and perhaps her smell across the road.

(…)

‘The Singularity, the second novel (and first to be published in English) by Balsam Karam … is evidence of the unique genius of human creativity…. Language is at the heart of The Singularity, moving as it does from chaos and cacophony to the simple purity of a single voice, which is one measure of its brilliance and its beauty.’

— John Self, Observer

‘The two narratives refract and then come together in a poetic convergence. There is a haunting, hushed tone to the novel, neatly evoked by Saskia Vogel’s translation from the Swedish, that probes the disorienting effects of exile.’

— Anderson Tepper, New York Times

‘Karam is a terrific prose stylist. Many of her sentences are surprising in their syntactical innovation and unique poetic rhythm. Like Virginia Woolf, Karam is interested in fragments, and in how they can fit and flow together. There is a choral quality to her writing, and a rich philosophical undertow to many of her observations…. The Singularity sweeps us along, offering profound wisdoms on motherhood and migration, war, home and grief.’

— Yagnishsing Dawoor, Times Literary Supplement

‘In Karam’s beautiful and harrowing English-language debut, a pregnant woman witnesses another woman plummet to her death from a promenade above the sea…. The slim, subtle, and somewhat abstract narrative gestures at grand tragedy in its depiction of the indifferent metropolis as “a hole between what came to be and what could have been,” where tourists pay little mind to a refugee’s for her missing daughter. This is powerful.’

— Publisher’s Weekly, starred review

‘Karam infuses this perceptive and compassionate novel with a sense of perplexity that perfectly matches the lives of those she portrays.’

— Declan O’Driscoll, Irish Times

‘The Singularity, deftly translated from the Swedish by Saskia Vogel, is an intense gem of a novel with a sophisticated structure. After a brave, even risky, prologue, which establishes the plot in a few pages, Balsam Karam moves deeper into the story of these anonymous women in an unidentified city who have been forced to flee their homes in an unnamed war.’

— Francesca Peacock, Spectator

‘Lyrical, devastating and completely original, The Singularity is a work of extraordinary vision and heart. Balsam Karam’s writing is formally inventive and stylistically breathtaking, and Saskia Vogel’s translation does shining justice to its poetic precision and depths.’

— Preti Taneja, author of Aftermath

‘I don’t know anyone who writes like Balsam Karam. She blows me away. Truly one of the most original and extraordinary voices to come out of Scandinavia in … forever. You’ll realize twenty minutes after you’ve finished this book that you’re still sitting there, holding on to it.’

— Fredrik Backman, author of A Man Called Ove

‘The Singularity by Balsam Karam is a novel about loss and longing – a mother who misses her child, children who miss their mother, and all of those who miss their country as they try to feel the new earth in their new land. A deeply moving work of fiction from a true voice of Scandinavia.’

— Shahrnush Parsipur, author of Women Without Men: A Novel of Modern Iran

‘Balsam Karam writes at the limits of narrative, limning the boundary of loss where “no space remains between bodies in the singularity”. With a lucid intimacy, Karam braids a story of witness and motherhood that fractures from within only to rebuild memory and home on its own terms. The Singularity is a book of conviction where those who have been made to disappear find light and keep their secrets too.’

— Shazia Hafiz Ramji, author of Port of Being

‘Astringent, fuguelike…. A knotty, sui generis evocation of mothers’ feelings of fear and loss.’

— Kirkus

‘The Singularity reads as a great argument for realism: Karam’s world and its characters are excellently rendered in its harsh light. Reading the novel, one is confronted with the fact that the most essential part of mothering – and humanity – is inconsistent with being a bystander.’

— Liz Wood, Word Without Borders

‘Ultimately, Karam’s book illustrates in vivid detail – in just 200 pages, intricate yet in accessible prose –the vivid trapped existence of refugees, of how they begin to live outside time and space, of how the world seems not to see or acknowledge their past or their presence, while denying them a future.’

— Rachel Leah Von Essen, Chicago Review of Books

‘It’s a free-flowing and intensely empathetic novel that seeks out submerged connections and, importantly, resists the easy clichés and tropes that sometimes diminish fictional portrayals of migrant experience.

— Sydney Morning Herald

‘The novel’s key achievement is in how it breaks the format of the multigenerational novel, with its well-worn progression from grandmother to mother to daughter. Karam is able to tell, in less than 200 pages, the multigenerational tale of two families in a surprising and nonlinear text of patterns and bleak repetitions, the rhythms of real life.’

— Emily McBride, The Rumpus

‘No need for spoiler alerts here: what might feature as the climax in a more conventional narrative is laid bare in The Singularity’s prologue. That it nevertheless remains absorbing to its very end is a testament to the depth of feeling and dexterity with which the Swedish-Kurdish novelist Balsam Karam orchestrates the rest of this novel about grief, loss, migration, and motherhood.’

— Rachel Stanyon, Asymptote

‘Ceaseless in form, and relentless in the movement of its sentences, The Singularity tracks the intertwined grief of these two women with an unwavering empathy and kindness, as they grapple with their own loneliness and grief in the wake of perpetual loss. In these lyrical meditations, Karam gets to the heart of what it means to be a mother haunted by the loss of a child, in a geography that is not one’s first geography. A novel about what it means to exist in a fractured, tenuous motherhood that is and is not, The Singularity examines what it means to collapse motherhood into itself, to look both backwards and forwards to negotiate a new self against a landscape that is fundamentally cruel, even as it glitters perpetually.’

— Vika Mujumdar, Massachusetts Review

‘The Singularity portrays the relationship between mothers and daughters in all its breathtaking, battling tenderness, in all its perils and unbreakable bonds. It describes the burden of being an immigrant in a place that has not the care or patience to welcome those forced by war to seek refuge. Devastating and brilliant.’

— Lulu Alison, Writers Mosaic

Balsam Karam (b. 1983) is of Kurdish ancestry and has lived in Sweden since she was a young child. She is an author, librarian and university lecturer, and made her literary debut in 2018 with the critically acclaimed Event Horizon, which was shortlisted for the Katapult Prize. The Singularity was shortlisted for the August Prize and is her first English-language publication.

Saskia Vogel is the author of Permission (2019) and the translator of over twenty Swedish-language books. She was awarded the Berlin Senate grant for non-German literature and was a finalist for the PEN Translation Award. She worked on The Singularity as part of her translation residency at Princeton University. From Los Angeles, she now lives in Berlin.